In 2003, Sotheby’s pulled out of the online art market claiming lower than expected profits. At the time, Sotheby’s CEO William Ruprecht told WSJ, “There are simply not as many people prepared to buy authenticated fine art online as we had hoped.” Some buyers are wary about buying art online, given the ease with which forgers and other unscrupulous dealers can take advantage of buyers. Especially given that in most cases, buyers don’t even have a chance to see the works before they make their purchase. But the true problem has more to do with the public’s obsession with a good story, than people getting bilked out of money from buying art online; at least no more so than traditional art purchasing options. Art forgeries capture the public’s imagination, fascinated by how collectors, galleries, and professionals could have been so misled, costing thousands or even millions of dollars; all furthered by the ease with which information spreads in the digital age. Look no further than the disagreement over the sale of a $46,000 painting that may have been a Caravaggio worth $15 million. Even if it turns out to be indisputably proven that the work was not from the hand of the great Master, the vast majority of the public will never hear that story, and Sotheby’s will never be exonerated. The online art market may be in the same state; “ A few bad eggs . . .“

Despite the bad press Sotheby’s received over the Caravaggio, it is a well-respected organization, tough enough to weather the storm. Sotheby’s, along with its competitor Christie’s and startup Artsy, seem to be among the few companies that currently dominate the online art market. To further that dominance, Christie’s invested $20 million in Christie’s LIVE, a digital platform allowing access to its live auctions online. The company has sold 83 works online, including Edward Hopper’s “October on Cape Cod” which sold for $9.6 million, setting a record for an online bid in an online auction. Sotheby’s recently decided to get back into the online market partnering with eBay. While those players make up a large part of the marketing in dollars, they actually sell very few items. Most collectors cannot afford Christie’s / Sotheby’s price level, and so turn to less respected online platforms, such as Auctionata, Paddle 8, and eBay. For these sites, sales or auction prices are typically in the $5,000- $15,000 range, along with fairly low commissions.

Unfortunately, these sites do not exercise the same control over their sales as Christie’s and Sotheby’s, and appraisals are too costly for a $15,000 work. With the online art market having a reputation for being a haven for forged art created by talented miscreants, or even more problematic, that the online art sites don’t particularly care about verification and validation of the works they sell, the market has been slow to grow. It is the uncertainty in provenance along with the after-effect from several high-profile forgeries that makes many collectors hesitant to purchase art online. The reality is, however, that while there is certainly some fraud, it remains only a small part of the online market, and as such, a low risk. Yet that fear is one of the major factors that has kept the online art market at a mere 5% of the total art market, according to the 2015 TEFAF Art Market Report.

Online sites have taken steps to combat fraud but the perception is much harder to dispel. Auctionata, for example, has a team of 300 experts that evaluates art before lots are offered at auction or in the Auctionata online store. As one of the largest online auction houses, the company sold over 12,000 objects in 2014. Nearly 8,000 bidders from over 100 countries placed bids for a total bid value of €250 million ($325 million). The company caught several forgeries prior to an auction, which has been overshadowed by several problem cases. (For more n Auctionata’s problems, see The Fine Art Blog) For example, one of its experts spent nearly three years in prison for fraud, after admitting to having ripped off more than a dozen people in the United States and elsewhere, through a series of fraudulent sales and consignment deals involving rare bows, violas, and violins. Auctionata has also been accused of poorly documenting some works, such as International auction results without links, inaccurately reporting conditions of certain pieces, and erroneously referencing the catalogue raisonnés documentation. Catalogues raisonnés are scholarly compilations of an artist’s body of work, which are critical tools for researching the provenance and attribution of artwork. The International Foundation of Art Research maintains a database of published catalogues raisonnés.

Auctionata isn’t the only online art seller that has had problems. Over fifty counterfeit Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, and Jean-Michel Basquiat lots were sold in 2014 by a Swedish eBay Seller. A counterfeit Richard Diebenkorn painting sold on eBay for $135,858 using shill bidding, (bidding on one’s own auction), which is strictly forbidden by eBay rules. In that case, the bidding for the counterfeit work started at a mere 25 cents, which did not raise any red flags. According to the FBI indictment, the listing said that the owner had bought the painting at a garage sale in Berkeley, California and that his child had punctured a hole in it with a Big Wheel. The listing had a picture of the hole, through which could be seen the initials “R.D.” In another case, four Keith Haring counterfeits were listed in auctions on Paddle8, where specialists had failed to conduct proper due diligence before listing the obvious counterfeits. Three of the paintings had accompanying letters that erroneously confirmed authenticity by Angel Ortiz, a graffiti artist and Keith Haring Collaborator, also known as LA2.

While these incidents certainly seem egregious and should have been caught by their respective online sellers, the forgeries must be put into perspective. The vast majority of works sold online are not forgeries, but more importantly, forgeries are not endemic to the online art market. Thousands of forgeries are found in the traditional art market as well. The only major difference is that customers get to see the traditional market forgeries before they are duped into buying them. For example, the Alexander Calder Foundation itself presented fake Calder works, which were sold by museums and galleries. Spanish art dealer Jose Carlos Bergantiños Diaz sold dozens of fake paintings from well-known artists such as Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell and Clyfford Still; all painted by an artist he met on a Manhattan street corner. The scheme stretched for nearly two decades and generated more than $30 million. Some have become so infamous that movies have been made about them. The Art of Forgery documents the life and times of Wolfgang Beltracchi, who tricked the international art world for nearly 40 years by forging and selling paintings of early 20th-century masters and Art and Craft, a documentary about one of the most prolific Forgers, Mark Landis, who duped nearly 60 American museums into accepting his facsimiles of artworks over a 30 year period.

Proper Provenance

So what can people do to protect themselves when buying art online, especially for those pieces that are too inexpensive to warrant appraisals? First and foremost, do what you can to secure the artwork’s provenance, which is the documentation that certifies the work’s authenticity. An ideal provenance history would provide a documentary record of owners’ names; dates of ownership, and means of transference, such as whether it was inherited or bought through a dealer or auction; and locations where the work was kept, from the time of its creation by the artist until the present day.

Also, check to see if the work has a Certificate of Authenticity (“COA”). The COA should be signed by either the artist who created the art, the publisher of the art (in the case of limited editions), a confirmed established dealer or agent of the artist, or an acknowledged expert on the artist. A legitimate COA must contain specific details about the artwork, such as the medium, (i.e. Oil on canvas, digital print, silver gelatin photograph, etc.), the name of the artist or publisher, the work’s title, the edition size (if it is a limited edition,) the artwork’s dimensions, and the title, qualifications, and contact information of the individual or company that issued the certificate. Both contact information and qualifications must be verifiable. Documents that do not specifically describe the piece of art in question do not constitute valid provenance. You should then cross-reference these with the catalogue raisonnes for that particular artist to ensure that it, at least, represents a known work by the artist.

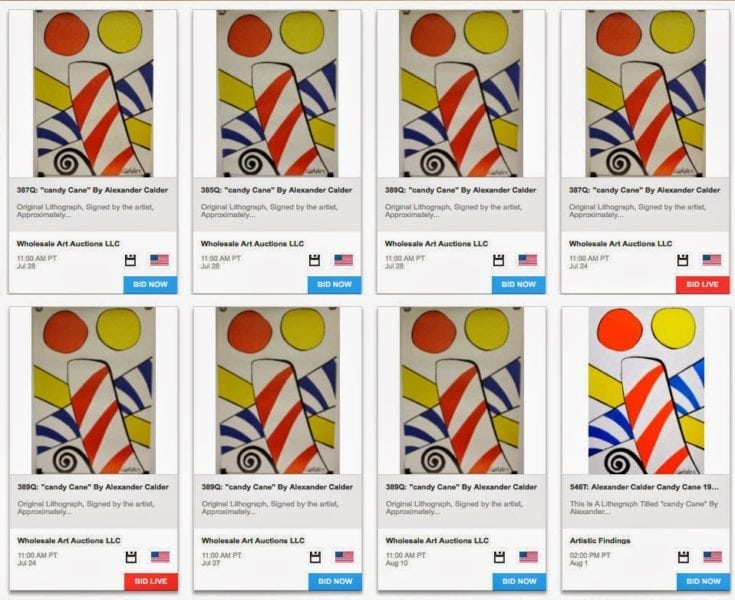

Fake Calders Sold on LiveAuctioneers.com

Unfortunately, in many cases finding such complete provenance is not available. Unbroken records of ownership are rare, and most works of art contain gaps in provenance. Many wealthy collectors wish to maintain anonymity, and many sales are done privately. In addition, many art transactions are documented with simple invoices, rather than detailed contracts. It is often unclear from the face of the invoice what exactly was bought or whether a dealer is acting as a principal or as an agent for another party. In that situation, any purchase decision is risky. The buyer can always get an appraisal, but be sure that the value of the work is discounted such that the appraisal fee does not add so much to the work that the buyer is overpaying. Any seller should know that the provenance is deficient and discount the work. If at auction, be aware of the appraised value when bidding. If there are any questions, then move on. There are always other works. If the price seems too good to be true, it probably is.

Unscrupulous sellers will often go to great lengths to manufacture or fabricate phony provenance for their art. The good news is that phony provenance is relatively easy to detect. Work your way back through the history, verifying the supposed sales or even matching signatures with other signatures available on the web. If the galleries that sold the works are still in business, contact them to confirm that the sales are legit, and verify other items or information listed. If none of the galleries or auction houses are traceable, then this may be cause for concern. So, while forgeries are rare as a percentage of total art sold, there is still a risk, but a risk that can be minimized with just a little legwork. But fear should not drive purchasing decisions. Do your due diligence. Before bidding or buying any art online, be as sure as possible that there is legitimate provenance, which is verifiable and does, in fact, attest to the authorship of the art.