Detecting art forgeries is extremely difficult and so remains a rampant issue within the art market. These highly technological tools to combat the practice are more important than ever.

On May 15, the Michigan-based art dealer, Eric Spoutz, will report to federal prison for selling fake paintings he claimed were by Willem de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, and others. Spoutz defrauded buyers out of nearly $1.45 million while also donating fake works to museums, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

The court ordered Spoutz to forfeit the $1.45 million and to pay $154,100 in damages, however, his extensive use of aliases makes it difficult to account for all the forged works. So far, the FBI has recovered about 40 forgeries and admits that there may be hundreds more sold to unsuspecting victims, mostly in Florida and on eBay.

Unfortunately, art forgery is becoming all too common. The Fine Art Experts Institute in Geneva has stated that between 70 to 90 percent of the pieces brought to them for examination are inauthentic, and based on their research, the Institute suggests that as much as 50 percent of artwork currently in circulation may be forgeries.

Granted, many of these are obvious forgeries or so underpriced that one should be skeptical. As of this writing, one hand-signed Andy Warhol lithograph is selling for under $800. Brian Swarts of Taglialatella Galleries, a major force in the global art community, is well versed in the secondary Warhol market. Tagliatlatella exhibits works from some of the most popular contemporary and modern artists, including Banksy, Jean-Michael Basquiat, Mr. Brainwash, Keith Haring, Jeff Koons, and, of course, Warhol. Swarts is highly skeptical that a hand-signed Warhol lithograph priced that low would be authentic. According to Swarts, even a lower-end, hand-signed Warhol lithograph would sell for at least $10,000 or more.

Forgeries not only affect buyers and sellers monetarily but have a profound effect on works throughout the market. Finding a forgery can cast doubt on the expertise of the authenticators and damage the reputation of the sellers. As a result of several high-profile forgeries, Sotheby’s recently became the first big auction house to create its own forensic art analysis department by acquiring Orion Analytical, a specialist on investigating high-level forgeries.

The art forgery of “Portrait of a Man”, courtesy of Weiss Gallery. Sotheby’s fake.

Sotheby’s has worked with Orion before. In 2011, Sotheby’s ran into trouble when it privately sold a 17th-century work by Frans Hals to a collector for $10 million. The work was consigned by Mark Weiss, a respected London dealer who had bought it from the French-Italian dealer Giuliano Ruffini for €3 million. After some concern over authenticity, the painting was sent to Orion Analytical to investigate its authenticity. The company’s forensic analysis revealed the presence of modern materials that could not have been used in the 17th century. Sotheby’s immediately rescinded the sale and reimbursed the buyer.

Given the considerable number of art forgeries, it’s no wonder that a company such as Sotheby’s would want to have forgery detection in-house. It’s a complicated area, with very good forgers able to fool the best art detectives. So, what techniques do these companies use? Are they effective? More importantly, are they expensive? Let’s take a look at a few of the most popular techniques for authenticating artwork.

Historical Research Can Combat Art Forgeries, But It’s Rarely Enough

Most forgery detection begins with research. It’s important to analyze whether the content of the work is truly from the time period in which the author lives. Painting the name on a storefront in a landscape painting that didn’t appear until after the artist’s death would immediately suggest a forgery. Much of these details can be found by looking at the provenance of the work or other details in the artist’s catalogue raisonné, or the retrospective body of their work.

Provenance

Regardless of what technique is used, every authentication starts with determining whether a work has a provenance, which is the record of a work’s ownership history. Ideally, the record should stretch all the way back to the work’s creation. For older works, this can be difficult, as proving valid recordation from 200 years ago is often a diligent, time-consuming task.

Unfortunately, an unidentified forgery will accumulate its own provenance the longer it goes undiscovered, so the provenance becomes increasingly reinforced as time passes. Forgers will often take advantage of loose provenance by creating an illusion of provenance along with forging the work. They will build a fraudulent identity for the work with fake documents and staged photographs. The longer the forgery goes undetected, the harder it may be to detect that the documents are not genuine.

For modern works, provenance is often much easier to verify, although, for less expensive works or limited edition lithographs, the cost of verification may be more expensive than the work itself. The result is a market of fakes that go unchecked.

The risk can be mitigated by buying works from a reputable dealer or gallery, who will likely have done the research prior to showing the works. Obviously, this is not a panacea, as seen in the forgery scandal that closed the Knoedler Gallery; however, situations like that are rare. Most well-respected galleries would be hesitant to ruin their reputation by even accidentally selling a forgery.

Catalogue Raisonné

A catalogue raisonné is a comprehensive, annotated listing of all the known works of an artist. They are usually set up as compendiums, sometimes by medium, date ranges, or work types (i.e., sculpture, watercolor, oil on canvas, and more). The catalogue provides important details about each work, including title, dimension/size, creation date, and current location. This is also where buyers can view a work’s provenance, along with a list of lost or destroyed works and known fakes.

Finding a fake may be as simple as checking to see if a work is listed as being owned by a particular collector who is not the one selling the work.

Unfortunately, the use of the catalogue raisonné can benefit the forger as much as the purchaser. Many forgers will consult the catalogue as a means of determining what to fake. A work listed as missing would be a perfect candidate for a forger who could not only produce the work with the corresponding characteristics but could also create accompanying documents that follow the known provenance prior to the work being reported as missing. If nobody investigates the document’s validity, the provenance continues without anyone discovering that the work is a forgery.

The Spoutz case mentioned earlier is a good example of someone who used the catalogue raisonné to promulgate the sale of a forged work. An FBI statement on Spoutz noted that he also owned a legitimate art gallery and understood the value of provenance. He forged receipts, bills of sale, letters from dead attorneys, and other documents. Some of the letters dated back decades and looked authentic, referencing real people who worked at real galleries or law firms. Spoutz also used a vintage typewriter and old paper for his documentation. Buyers assumed that Spoutz had authenticated the works and relied on Spoutz’s reputation. Spoutz didn’t just sell fake works but created a believable narrative based on known information about the artist and common human behavior.

Non-Invasive Techniques for Detecting Art Forgeries Are Becoming Increasingly Popular

Ultimately, Spoutz’s forgery operation was discovered not by referring to gaps in the work’s provenance or discrepancies with the catalogue raisonné, but through scientific methods of authentication.

Using scientific methods for authentication is often a multi-layered endeavor. The first line of authentication utilizes non-invasive imaging techniques, such as Optical Imaging, X-ray, Infrared, or UV light, that won’t damage a work.

UV Florescence

UV-induced visible fluorescence imaging is most often used to authenticate historical paintings but can be used in other mediums, as well. As they age, paints and varnishes develop fluorophores, a fluorescent chemical compound that, when irradiated with long-wavelength UVA lamps, will show areas of luminescence. In layman’s terms, the original work will shine brighter than retouched or restored areas.

Optical Microscope

Virgin and the Child with an Angel by Francesco Francia (1450–1517)

The optical microscope allows the user to see the fine details on the surface of a work, from brushstrokes and the craquelure in varnish to the ink patterns of a lithograph. Imperfections or an attempt at mimicry can become detectable under high magnification. Take, for example, the Virgin and the Child with an Angel by Francesco Francia (1450–1517) that the National Gallery acquired in 1924 as a bequest from a wealthy businessman who had allegedly purchased it from a Roman dealer. Any earlier provenance was unknown. In 1954, a second version of the painting came up for auction in London. Both versions were examined using optical microscopy, which revealed painted cracks on the surface of the 1924 version, as well as fine pencil lines in some of the detailed areas. These artistic techniques were not used in Renaissance paintings, suggesting that the 1924 version might be a forgery, although the finding remained controversial.

X-Rays

Traditional x-rays are also used to unearth hidden figures and materials underneath the surface of a work, particularly metallic and non-organic materials. As a result, many historic paintings show a ghost-like image under X-Ray but can also reveal an artist’s revisions or even abandoned compositions on a re-used canvas.

For example, prior to 1910, the white basic pigment used to dilute and create various colors contained lead carbonate, so a pre-1910 painting without any lead white pigment is likely to be a forgery. The Fogg Art Museum had in its collection a Portrait of a Woman by Francisco de Goya. In 1954, an x-ray revealed the canvas had been re-used and underneath the painting was another portrait. Additional analysis showed that the buried painting contained zinc white paint, which didn’t exist when Goya was alive.

Infrared Reflectography

Another optical approach is infrared reflectography, a technique that fires wavelengths of radiation into the artwork to reveal what’s underneath the surface. Artist materials are somewhat transparent, so by using long-wavelength radiation, we can see through them into each of the underlying layers.

Before commencing work, painters often sketch the scene on the canvas and with Infrared cameras, and we can see these initial drawings. Infrared can also show the height of the craquelure and its pattern across the surface of a work. Naturally occurring cracks create a pattern perpendicular to radiating lines of stress that originate in the corners of the canvas on a frame. Faked cracks not related to stresses, on the other hand, are detectable in the infrared image.

As discussed earlier, the authentication of the Francia painting at the National Gallery remained controversial, but in 2009, infrared reflectography was used to discover that the forger had sketched the National Gallery’s version with graphite, a material that wasn’t available during Francia’s lifetime.

Invasive Techniques Are the Most Technologically Advanced – and Expensive

Sometimes, light-based non-invasive techniques are not enough to authenticate a work, so more invasive and destructive methods are required. These processes usually involve removing small pieces from the edges of artwork to analyze the elemental content of the medium. The predominant methods use some variation of “mass spectrometry” to find the quantities of certain molecules in the samples. Any molecules detected that is not expected as a constituent of the art materials from the time- period in question will indicate a forgery.

RadioCarbon Dating

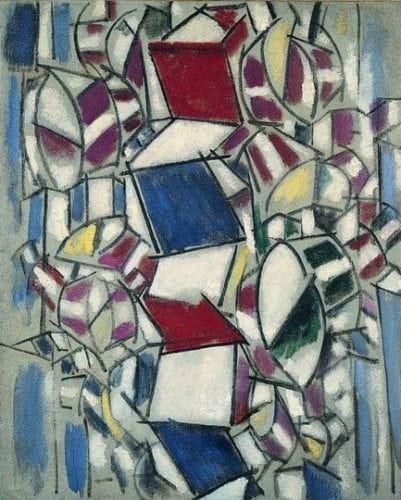

Fernand Leger, Contraste De Form

There were approximately 2,000 nuclear bomb tests between 1945 and the Nuclear Test Ban treaty in 1963, which prohibited the testing of nuclear weapons in outer space, underwater, or in the atmosphere. Those nuclear explosions caused small amounts of radioactive isotopes, such as cesium-137, carbon-14, and strontium-90 to cover the earth. These isotopes contaminated the world’s soil, including flax and linseed oil, which are both used in the production of modern paint. So, paintings created after the initial nuclear tests should contain these isotopes. Placing paint material into a mass spectrometer will show the levels of these isotopes. If there are too many isotopes in the sample, then the painting must have been made after 1945.

This practice was used in 2014, scientists from Italy’s Institute of Nuclear Physics used these radiocarbon tests to show that a Fernand Leger, Contraste De Forme, (1913-1914), from the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, was a fake, created no earlier than 1959. By comparing the radiocarbon levels known during the “Bomb Peak” between 1950 and the early 1960s, the team was able to conclude that the cotton plant used to make the paint was cut after Leger’s death.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight-mass spectroscopy (MALDI–TOF–MS)

MALDI–TOF–MS identifies molecular species and elements in samples based on their mass. The mass spectrometer provides a graph of the mass of the materials in the sample, which is then compared with a reference chart to determine differences from what is expected if the work was authentic.

It’s a fairly complex, three-step process in which a sample of the work is crushed and mixed with a matrix material so it can be applied to a metal plate. Then, a pulsed laser irradiates the sample, allowing the base materials to come to the surface. Finally, the molecules are subjected to an electric or magnetic field, and a mass spectrometer is used to identify the molecules.

In 2005, the son of a close friend of Jackson Pollock discovered thirty-two alleged Pollock works in his parent’s attic. A team at Harvard University’s Center for the Technical Study of Modern Art analyzed three of the works using MALDI–TOF–MS and found three pigments in the binding media that were not available during Pollock’s lifetime (1912–1956).

Peptide Mass Fingerprinting (PMF)

Peptide mass fingerprinting (better known as PMF) is a data-crunching method that uses the MALDI-TOF-MS to analyze animal proteins on a molecular level. Many art materials, especially those used in historic works, used animal tissue for things like paint binders, adhesives, and coatings. Until recently, there was no method to identify the type of animal tissue used. PMF changed that. After analyzing samples from artwork, the PMF technique creates a “fingerprint” of the organic matter, which can then be compared to those found in various animal tissues, like egg yolk (used in tempura), to find matches.

The Wedding Dance in the Open Air by Pieter Brueghel the Younger

__________

Although some of these techniques are expensive, they are beginning to work their way out of the top markets and into lower-end works. They also aren’t just used for forgeries since they can additionally authenticate previously mislabeled works. For example, at the Holburne Museum in Bath, a work attributed to a disciple of Pieter Brueghel the Younger was recently reattributed to Brueghel the Younger himself. “The Wedding Dance in the Open Air,” a painting bought by Sir William Holburne in the 19th century, was originally attributed to Brueghel the Younger, but its attribution had been cast into doubt by a director of the museum in the early 20th century. Using Infrared imaging (and careful cleaning of the work), a drawing was revealed underneath the work that help conclude it as an authentic Bruegel the Younger.

If you want to know more about art forgery and happen to be near Delaware’s Winterthur Museum, you can see some of these techniques firsthand. The museum is currently running “Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes,” which illustrates the ongoing battle that pits clever forgers and con-men against equally determined art conservationists and historians. The exhibit, which runs through January 7th, offers a firsthand look at how experts detect high-priced fakes and forgeries.

These are only a few of the techniques, as many more are being discovered every year. Forgery is a big business, and so is the market to battle the forger. A lot of resources are being thrown at the problem and while it seems to be working, criminals like Spoutz will continue to pull off lucrative art forgery.