When we purchase an item, whether it’s a blender, a set of golf clubs, or that cool new Apple Watch, we own it. By ownership, we mean having the exclusive right to possess, use, control, and dispose of a physical object. If the owner wants to take a sledgehammer and destroy that beautiful new car, It’s their choice. That’s not the case, though, when it comes to art and design.

When a person or a business purchases a corporate logo or commissions a mural for a hotel lobby, the ownership rights are not the same as owning a physical item. Creative work is considered intellectual property. This distinction is crucial. Intellectual property (IP) refers to intangible creations of the mind, like artwork, designs, inventions, and literary works. Unlike a tangible object like a car, intellectual property doesn’t have a physical presence.

When purchasing creative work, the buyer receives a license to use the work for specified purposes, not ownership of the work. The copyright holder — often the freelance artist or designer — retains ownership and determines which rights are granted by the license. This concept can be confusing, especially since intellectual property often presents itself in a physical form.

Let’s take this hypothetical scenario:

A commercial real estate agency, amidst a branding overhaul, enlists a freelance artist to create a series of drawings. These illustrations, capturing the essence of local streets and buildings, are meant to enhance the agency’s website and form a key part of their marketing campaigns. The agency, appreciating the aesthetic appeal of these drawings, also turns them into posters for office decoration and occasionally gifts them to clients.

To their surprise, these posters became immensely popular, leading the agency to sell them on their website. This venture turns out to be more than just profitable; it significantly boosts their client engagement and property sales. However, when the freelance artist discovers the sale of these posters, a conflict arises. The artist had not authorized the sale and subsequently demanded a halt to this activity, along with a licensing fee for the already sold posters. The agency, on the other hand, argues that their payment for the designs entitles them to unrestricted use, including sales.

As you can imagine, many lawsuits are fought over ownership rights for artistic works and other intellectual property, many of which would not have happened had the parties known the basic rules surrounding IP ownership.

Copyrights

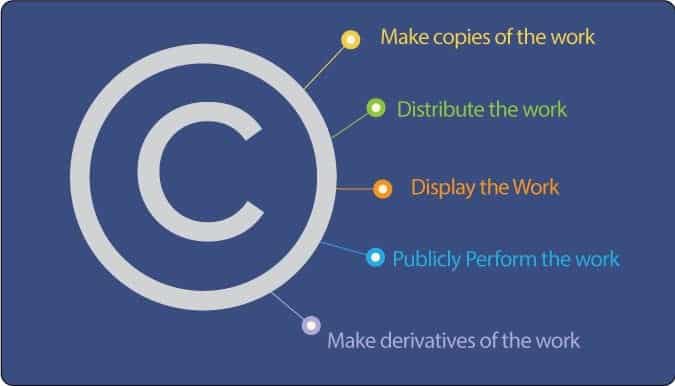

Let’s first look at the rights afforded by copyright ownership granted to creators via the U.S. Copyright Act. Copyrights form the core of an artist’s legal protection, granting them a set of exclusive rights to their work, each empowering them to control how their work is used, disseminated, and transformed.

Let’s unpack this treasure chest of artistic control:

-

The Right of Reproduction: This right grants the artist exclusive authority to create copies of their work, whether as physical reprints or digital reproductions. If the agency produces posters for sale without the artist’s permission, it infringes upon this fundamental right.

-

The Right of Distribution: This right serves as a gatekeeper, enabling the artist to determine how and where their work is disseminated to the public. Using the artwork on the agency’s website and in marketing materials might align with the initial agreement, but selling the posters ventures into a new distribution channel, requiring a separate license.

-

The Right of Derivative Works: This right allows the artist to control any alterations or transformations of their work. For instance, adapting the street drawings into a city map without the artist’s consent would constitute an unauthorized derivative work.

-

The Right of Public Display: This right gives the artist control over how their work is displayed publicly. Displaying the artwork in the agency’s office and on their website may be covered under the initial agreement, but if they were reproduced and hung in a hotel lobby, that would likely require additional permission from the artist.

-

The Right of Public Performance: While typically associated with performing arts like music and theater, this right can also apply to certain types of visual art displays, especially in digital or multimedia formats. It governs the public showing of the work and may require separate permissions depending on the nature of the performance or display.

-

Moral Rights (depending on jurisdiction): In certain jurisdictions, artists maintain moral rights over their work even after sale. These rights can include preventing the distortion or mutilation of the work and opposing its association with activities that could harm the artist’s reputation or integrity. These rights are crucial in maintaining the respect for and integrity of the artist’s creative vision.

The rights that the freelance artist grants are a matter of agreement and can be negotiated. This means they can license out different aspects of their work, like reproduction or distribution rights, while still holding onto others. It’s a flexible arrangement that allows for a variety of creative and commercial uses.

Usage rights are crucial in freelance artist agreements, defining the scope of how and where the work can be used.

In our scenario with the real estate agency, the initial agreement likely granted the agency the right to use the drawings for specific marketing purposes, such as on its website and for the company’s marketing materials. That is the reason they were commissioned. Even creating the posters for the office and giving them away as free gifts fall under the marketing materials license. However, the leap from using these drawings for marketing to selling them as posters is a significant one. It’s not just a different use; it’s a commercial venture that was probably not covered in the original agreement. Unless explicitly stated, the agency’s right to use the artwork would not typically include the right to sell it.

The artist, in this case, has every right to request a licensing fee for this new use of their work. Moreover, if the matter were to go to court, the artist could potentially claim a portion of the profits from the poster sales. It’s a clear example of how the nuances of intellectual property rights can play out in the real world, often catching purchasers off guard when they step beyond the bounds of the original agreement.

To prevent misunderstandings, it’s essential for freelance artists and other creatives to explicitly outline the permitted uses of their work in their written agreement with the purchaser. This approach not only clarifies the scope of usage for the purchaser but also opens the door for discussions about potential future uses. It also sets the stage for negotiation of terms, including any licensing fees, for uses that fall outside the original agreement.

In many cases, though, especially with companies, it will be the purchaser who drafts the agreement. In such cases, the artist must meticulously examine the terms. They should be particularly vigilant for a specific clause that, if included in an intellectual property agreement, transfers the entire copyright from the creator to the purchaser. This clause effectively grants the purchaser complete control over the work and is known as a Work Made for Hire.

Work Made for Hire – Freelance Artist

Typically, when an artist creates a work, they automatically hold the copyright. However, a Work Made for Hire agreement alters this norm, transferring copyright ownership to the employer or the person who commissioned the work. This transfer is not automatic and requires specific conditions to be met.

For a work to be a Work Made for Hire:

- Both parties must sign a written agreement;

- The agreement must specifically state that the work is Work Made for Hire.

The Supreme Court has held that work can be classified as ‘for hire’ if it is specially ordered or commissioned. This determination hinges on the “instance and expense” test. By “instance,” the court looks at how much direction or authority the hiring party has in guiding and overseeing the creation of the work. In examining the “expense” aspect, courts look at the nature of the payment. A fixed payment often suggests a work-made-for-hire scenario, while a payment structure based on royalties tends to indicate otherwise. Finally, even if the “instance and expense” criteria are met, the presumption of a work being for hire can be countered only with evidence of a contractual agreement specifying a different arrangement.

The Supreme Court determined that a work can be deemed for hire when it is specially ordered or commissioned. Courts have articulated an “instance and expense” test for determining if a work is a work for hire. Under this test, a work is made for hire if it was incurred at a hiring party’s “instance and expense.” The Second Circuit has further explained that a work is made at a hiring party’s instance and expense when the employer “induces the creation of the work and has the right to direct and supervise the manner in which the work is carried out.

In our scenario, assuming the agreement specifically stated that the drawings were “work made for hire,” whether the drawing would actually be considered made for hire would depend on how much direction was provided by the agency. The direction doesn’t have to be extensive. If the agency suggested the streets to be illustrated, provided reference material, or even suggested a style, that would lean toward a work made for hire. On the expense side, if the drawings were sold for a fixed price but also included royalties for the sale of the posters, then that would lean against the work being made for hire.

Assignment of Copyright

If a person or company wants to own the copyright, an artist can transfer the copyright at any time, regardless of work-for-hire terms. Imagine this scenario:

A designer creates a logo for a small company and charges very little due to the company’s financial status as a startup. Assume the company grows into a major entity with a well-recognized logo that emblazons on millions of T-shirts and other merchandise. The designer could rightly ask for licensing fees for the additional use.

No company wants that situation, but at the time the logo was created, the company didn’t have the funds to buy the copyright. However, at any time, the company could purchase the copyright, assuming the designer agrees. To ensure the company’s ability to purchase the logo copyright at a later time, it could have negotiated in the original contract to buy the copyright at a specific price. The point here is that while the artist retains the copyright to a work, the artist can give any part of those rights or all the rights away at their discretion.

Below is a sample Assignment of Copyright Agreement. Note that each artistic work should be listed as part of the assignment, and a high-resolution color version of each work should be attached to the document, with each initialed by the copyright holder.

ASSIGNMENT OF COPYRIGHT

[Company Name]

[Company Address]

This Agreement is made between [Hiring Company] and [Copyright Holder] whose address is [Copyright Holder’s Address]. [Copyright Holder] represents and warrants that he/she is the copyright owner of [Artwork Name or Names] designed and created for the [Hiring Company] (the “Work”) described and/or included in Attachment A and holds the complete and undivided copyright interest to the Work. For valuable consideration which is hereby acknowledged, [Copyright Holder] and [Hiring Company] agree as follows:

[Copyright Holder] does hereby sell, assign, and transfer to [Hiring Company], its successors and assigns, the entire right, title and interest in and to the copyright in the Work and any registrations and copyright applications relating thereto and any renewals and extensions thereof, and in and to all works based upon, derived from, or incorporating the Work, and in and to all income, royalties, damages, claims and payments now or hereafter due or payable with respect thereto, and in and to all causes of action, either in law or in equity for past, present, or future infringement based on the copyrights, and in and to all rights corresponding to the foregoing throughout the world.

[Copyright Holder] agrees to execute all papers and to perform such other proper acts as [Hiring Company] may deem necessary to secure for [Hiring Company] or its designee the rights herein assigned.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, the parties have executed this Agreement, effective this _____ day of __________________________ , 20___ .

[Full Name of Copyright Holder]

By: ______________________________

[Name] ______________________________

[Title] ______________________________

Date: ______________________________

Work Made for Hire – Employees

The second Work Made for Hire scenario is for work created as an employee in the scope of their employment. That means that the copyright for any work created on the job is held by the employer, not the artist. The concept may seem rather straightforward, but as with most legal rules, there are gray areas. In this case, the question is, “What is an employee?” Under the Law of Agency, labeling someone as an employee doesn’t necessarily make that person an employee.

The employer-employee relationship is determined by more than just getting a salary.

The Supreme Court has ruled that employment status is determined by the level of control a company has over the person’s work. Some factors courts will look at to decide whether someone is an employee include:

- What are the skills required to create the work?

- Who provides the necessary tools?

- Where is the work created?

- How long has there been an employer/employee relationship?

- Does the employer have the right to assign projects to the employee without consultation?

- Does the employee have predefined working hours?

- How is the employee paid?

- Does the employee receive benefits?

Companies often hire artists and designers as salaried employees but don’t give them the same benefits expected as a full-timer. In our scenario, hiring freelancers for a one-time job that is being completed off-premises for a specified price clearly makes the freelancers independent contractors, and not employees. Conversely, a graphic designer who works on-premises and gets paid a regular salary has a company-purchased laptop and has healthcare benefits would be an employee. In that case, the company would hold the copyright for any designs produced.

However, if the company had hired the graphic designer for a lengthy project and was given a salary on the same schedule as other employees, but they had to supply their own equipment, did not receive any benefits, and the designer wasn’t bound by certain policies like work hours or vacation days, then having a salary likely wouldn’t be enough to be considered an employee. So, the copyright for any work produced for the project would be held by the designer.

Summing It All Up

Hopefully, with all that we have discussed, it should be clear that the posters being sold by the company are a copyright violation, and the freelance artist has every right to ask for additional fees or sue the company for copyright infringement. Since there isn’t an employee-employer relationship, the company should have either created a work-made-for-hire agreement or, at some point, purchased an Assignment of Copyright from the artist so they could sell the posters without paying royalties, licensing fees, or incurring other additional costs.

________________

The moral of the story is that buying intellectual property, whether commissioning art or commercial graphic design, does not always mean that the purchaser fully owns the work. Instead, the purchase is nothing more than a limited license with terms dictated by the copyright holder. Should a purchaser need additional rights, consider one of the various methods discussed here. In either case, the only way to truly know what is really being purchased is to create an agreement that specifies the scope and breadth of the transfer of the rights, in sufficient detail so that both the creator and buyer know what is being bought and sold.

Have you encountered similar situations in your work or dealings with intellectual property? Share your experiences and thoughts on how these legal nuances impact the relationship between a freelance artist and a client.