Artist Richard Prince‘s new series of Instagram photos has been the internet’s topic of conversation over the past week. Why such a ruckus? In the series, Prince appropriates photos from the Instagram accounts of various celebrities, models, and other beautiful people. After blowing them up to gallery size and adding a few Instagram styled comments at the bottom, he sells them for a whopping $100,000 each, without permission nor providing any compensation to their owners. On first glance, the whole things seems more like a practical joke or maybe an article from the Onion, but it is all true.

As Peter Schjedahl wrote in the New Yorker, “The subjects include the generally known (Kate Moss), the semi-known (the art dealer Tony Shafrazi), and unknown (until now) folks advertising themselves in racy selfies or in a type of portrait that might be termed “the assisted selfie.” Reproduced bits of comment threads tend toward the slangy and the salacious. “Let’s hook up next week. Lunch, Smiles,” Prince responds to a voluptuous Pamela Anderson.” The works were originally shown at the Gagosian Gallery in New York City last October, but didn’t get much attention until they were prominently exhibited at the Frieze Art Fair last week.

Social Media and Appropriation Art

On the one hand, the appropriation culture has always blurred the lines defining what is considered art. So how is this any different that what has happened in the past? For example, in 1917, Marcel Duchamp submitted a store-bought urinal, which he titled “Fountain,” to an art exhibition, under the pseudonym, Richard Mutt. Beatrice Wood, one of the editors on staff for The Blind Man, no. 2 (May 1917), a modernist art magazine, commented at the time, “Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under a new title and point of view (and) created a new thought for the object.”

The Museum of Modern Art in New York sees appropriation art this way; “Pop artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselman, and Roy Lichtenstein reproduced, juxtaposed, or repeated mundane, everyday images from popular culture—both absorbing and acting as a mirror for the ideas, interactions, needs, desires, and cultural elements of the times. As Warhol stated, “Pop artists did images that anyone walking down the street would recognize in a split second—comics, picnic tables, men’s pants, celebrities, refrigerators, Coke bottles.” Today, appropriating, remixing, and sampling images and media is common practice for visual, media, and performance artists, yet such strategies continue to challenge traditional notions of originality and test the boundaries of what it means to be an artist.”

So for those who cry that Prince’s work is not art or that he is merely a thief, should remember that art is subjective and ephemeral, appearing in forms that sometimes seem to disparage, malign, defame or denigrate society. Today, Duchamp’s Fountain is iconic, considered the start of the Dada movement. It was voted the most influential artwork of the 20th century by 500 selected British art world professionals.

Duchamp’s Fountain

On the other hand, there are still legal boundaries that art shouldn’t cross. Someone claiming child pornography is art will still go to jail. Most cases are not that clear cut, though. Consider graffiti art. Can an artist receive copyright protection for an artistic work created while committing the crime of trespassing?

Copyright law also has many gray areas. Social media, for example, is full of reposted content taken from news sites or blogs, usually without permission. One would be hard pressed to find an art exhibition today where a significant number of spectators aren’t viewing art through cell phone lenses and posting their favorites on social media. From a legal standpoint, each photo is a copyright infringement but from a practical standpoint, suing the infringers is counterproductive. Not only will the lawsuit be cost prohibitive, but lawsuits would alienate the audience and likely prompt an internet backlash. Plus, it’s free promotion, anyway.

As well, copyright law only protects and artists work where the infringement generate significant income, otherwise, enforcing the law is not worth the legal fees involved. Richard Prince understands that concept very well, stating in a 2011 interview; “for most of my life I owned half a stereo so there was no point in suing me, but that’s changed now and it’s interesting”.

So while the question everyone keeps asking is whether Prince’s works are legal, the better question is whether it even matters?

Prince knows that his Instagram photo series may be illegal, but for him, and for the Gagosian gallery who is supporting the series, it’s merely a risk / benefit analysis. Prince weighs the possible outcomes against the potential rewards. If the benefits heavily outweigh the risks, then artists like Richard Prince will steal to the heart’s content, with no care as to ownership.

Prince’s Risk / Benefit and Fair Use Analysis

How does a risk analysis work for Prince and Gagosian? Let’s start with the law. Prince claims his work falls under a copyright exception known as “fair use,” which permits limited use of copyrighted material without acquiring permission from the rights holders. Fair use is an important concept that promotes free speech and creativity. Copyright law, if given its broadest interpretation, will often stifle artistic expression. So the courts needed to find ways in which the rights of the copyright holder could be maintained while at the same time allowing new forms of art to take shape for the benefit of society.

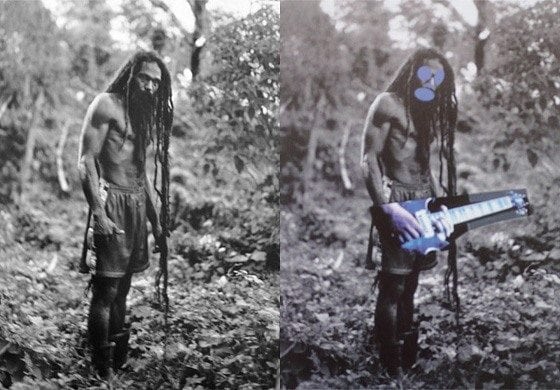

Prince knows quite a bit about fair use, probably more than any other artist and many Intellectual Property lawyers, as he was the defendant in a landmark fair use case; Prince v. Cariou. Between 1994 and 2000, Patrick Cariou, a photographer living in Jamaica, began photographing the island’s Rastafari, which he later turned into a book, “Yes Rasta.” Prince manipulated dozens of Cariou’s photos to create new works, although many felt that the changes were so minimal that Prince was infringing on Cariou. For example, Prince would paste other pictures on top of Cariou’s photos or paint over certain portions. In 2008, the Gagosian Gallery exhibited the series which Prince entitled; the Canal Zone. After a five year legal battle, Prince prevailed but the legacy of the case changes to the analysis used to determine fair use. If Prince’s work is considered fair use, it will be because of the results of that case.

Cariou v. Prince

Prince knows the rules and understands the arguments that will be required to defend himself. He created his works accordingly, albeit straining the edges of those defensive arguments.

Fair Use

Fair use is determined by balancing several factors:

1) The Purpose and Character Of The Use is usually considered the most important. The use of the copyrighted material must be transformative; the question the court asks is whether the new work changes the meaning of the copyrighted work for a new audience. This is the factor that most commentators seem to be hanging on regarding Prince’s work. It may be transformative in the sense that it is being taken from the phone to the gallery, with some additional comments at the bottom. But is it really a new audience? Aren’t the majority of people buying the works buying them because they are Instagram users? For those that have never taken and Instagram photo, would Prince’s works even be interesting?

2) Amount And Substantiality Of Portion Used looks at both the amount of the copyrighted material being used in a particular work. The artist must use as little of the copyrighted works as necessary to create the new work. For Prince, this factor may weigh in his favor. He could not have used less than the entire image to create his art, however, he is not altering the image at all. Even the minimalist changes he made to Cariou’s work were far greater than what he has done with his Instagram portraits.

3) Nature Of The Copyrighted Work considers what type of new work is being created? The Courts will consider factors such as whether the work is informational, just entertaining, benefits the public or spreads new ideas. How this factor will play out depends on the messaging Prince places on the work. Prince may say that he is commenting on the photos themselves or that he is using them to express something about society. How a judge or jury may respond to Prince’s commentary is hard to guess.

4) Effect of The Use On The Potential Market looks at the effect using copyrighted material will have on the potential market for the copied work. Does the new work cannibalize sales of the copyrighted work? The Instagram photos were never intended to be sold, so from that perspective, Prince isn’t cannibalizing anyone’s sales, however, he is selling the works for $100,000.

So is Prince’s work fair use? A case can be made for either side although, in my opinion, the case weighs against Prince. However, before suing, there are practical matters that need to be considered.

Fair Use May Not Matter

Suing Prince over his works is not a slam dunk, and as such, any action against him can take years with several obstacles that need to be overcome. Let’s look at a few. First, only the copyright holders are allowed to sue. In the majority of the Instagram photos at issue, the people in the photos are not the copyright holders. The photographers are the copyright holder, unless the photos were selfies. So the subjects of the photos may not have the right to sue unless the photographer transfers those rights. In other cases, the photographers may just be someone who snapped a photo on his or her iPhones, and may not even realize they took one of the photos being used by Prince. There may be some hesitancy on the part of photographers to sue over use of a photo they may not even want to be associated with. How many photographers would even consider suing? A few, at most.

For example one of the project’s photos was a selfie by a woman named Doe Deere. Commenting on her Instagram photo, Deere wrote that she never gave Prince permission, but she isn’t planning on taking action over the usage. (In an interesting twist, Deere herself has faced criticism for repackaging beauty products from other brands and selling them at a markup. Her brand, Lime Crime, has done exceedingly well despite complaints from customers over stolen credit card information after buying from her site.)

Next we have to weight the cost and time required for a suit. It could take quite a while, as evidenced by Prince’s last lawsuit. Anyone who chooses to sue will need to layout legal fees until they receive a damage award or settlement. The problem is that the maximum potential damages may not be high enough to justify a suit. The maximum damage award will be the profit, not the gross sales. With sale prices for Prince’s work hovering around of around $90,000, the profit may be less than the legal fees.

As well, for works that aren’t sold, there are little, if any damages. The copyright holders can send cease and desist letters, but that also will requires outlays of legals fees, yet without a sale, there is no monetary damage. If Prince ignores the demand, then there is little that can be done, at least until the image is sold. “One of the photos already included in Prince’s show, for example, originally came from artist Donald Graham, who subsequently sent a cease-and-desist letter. But Prince sourced it from a different Instagram account, @rastajay92, which had sourced it from another Instagram account, @indigoochild. And yet Prince was hit with the cease-and-desist while the two Instagram accounts weren’t, despite being the only one of the 3 appropriators to have made any changes to the photo.” [1] Prince ignored it.

Even if one of the subjects does decide to sue and it seems that the case isn’t going well, Prince can always offer a settlement, one that is high enough for a person to take it to avoid the long litigation, and at the same time, still have some profit. Of course, the settlement is only for one photo. Any profits made on those photos which are not part of the lawsuit would generate full profits for Prince and Gagosian.

So far, this analysis suggests that there is actually little risk for Prince.

Right of Publicity

One last hurdle however, is a non-copyright related legal issue; Prince and Gagosian may be violating a person’s right to control the commercial use of their identity, also known as the right of publicity. The laws pertaining to publicity rights are a bit different in each state. Only about half the states recognized a right of publicity although some states require that the person be of a celebrity stature. This case would most likely be held in the courts of New York, which is among the states having laws most beneficial to the person being exploited. Under New York law, a person’s name, portrait, picture, and voice are protected, regardless of their celebrity status.

To prove that there is a violation of a right of publicity, the person’s identity must be 1) exploited within New York State; 2) used for something being sold; and 3) used without written consent. The law provides for injunctive relief, which means the person can have the artwork removed from the public eye and monetary damages to compensate for the emotional distress caused by the use. Proving that someone is emotionally distressed over the use of their photo in a gallery is a difficult hurdle.

The law also allows a person to recover punitive damages, which are designed to deter further violations. Generally though, courts don’t like to give punitive damages unless there is a clear intent on the part of the defendant to disregard the law. Usually, the law is designed to make a plaintiff whole, but not enrich them. So counting on punitive damages is not a good idea,

______

It seems then, that there is little downside for Prince or Gagosian. As Michael Zhang at Peta Pixel put it; “There’s no reason for the reproductions to exist, except to make Prince a little cash.” If Prince analyzed the potential legal issues as I suggest, then he would have found the risk acceptable. As mentioned earlier, the question people should be asking is not whether Prince may be committing copyright infringement, but whether copyright law even matters in a case like this? The cut and paste digital world will continue to stretch the boundaries of what is art and test the legal frameworks that protect artists. So maybe a better question is, can copyright law handle the digital revolution or is it time for an overhaul?