We’re excited to feature Achim Weinberg, the winner of our “The Infinite Loop” open call. His work draws from the quiet elegance of natural forms—circles, cells, and everyday curiosities—reframing the familiar into something intricate, unexpected, and full of life.

What do grapes, hair curlers, and geometric divisions have in common? In the hands of German artist Achim Weinberg, they’re all part of a lifelong exploration of structure, individuality, and the curious patterns of growth.

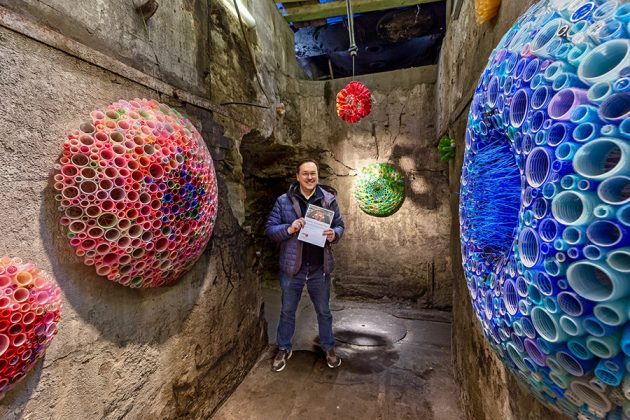

Achim Weinberg at the “13th Revierkunst 2025” exhibition in Germany’s Ruhr area, surrounded by his cellular, color-rich forms. He received 2nd prize at the Revierkunstpreis.

Born into a creative household, Weinberg grew up surrounded by art and design. His father—an artist, inventor, and graphic designer—filled their home with works by Daumier, a Picasso lithograph, reproductions of Paul Klee, and a deep respect for Bauhaus and classical modernism. “By the age of 14, I knew I wanted to become an artist,” Weinberg says. He had already been drawing portraits, experimenting across mediums, and making full use of his father’s photo studio, wood and metal workshops, and darkroom.

His early formal training in painting was influenced by Francis Bacon and figurative work, but a pivotal shift came through the influence of Professor J. P. Hölzinger. “I was particularly impressed by the Zero artists and architects like Mies van der Rohe and Tadao Ando,” he recalls. That architectural minimalism and structural clarity continue to echo through his work today.

Inside Achim Weinberg’s studio, where everyday curlers become cosmic systems—each drawer, wall, and tabletop a catalog of curiosity and circular thinking.

Since the 1990s, Weinberg has been deeply immersed in one particular form: the circle. His fascination began with a question—why do so many human-made structures rely on right angles, when the natural world so often leans toward curves, spirals, and spheres?

Round forms, he notes, dominate the microscopic and cosmic: atoms, diatoms, fruit, planets, coral, and even the seeds that sustain plant life. “All the forms of life amaze me,” he says. “Perhaps I can pass on my enthusiasm through art.”

That sense of wonder runs through all of his work, especially in how he selects materials. Weinberg doesn’t just find materials—he notices them. “Whether it was cotton buds or honey or grapes, it’s this phenomenon where you suddenly perceive something you’ve seen a thousand times with different eyes,” he says. “That experience was strongest with the grapes.” Cutting them into his yogurt one morning, he suddenly saw them as individuals—unique, complex, and alive. That spark led to an entire body of portraiture, with each grape assigned a name, personality, and place in a larger story.

His choice of curlers—yes, the kind found in your grandmother’s bathroom drawer—was similarly intentional. He was looking for something round, transparent, and ordinary. “I wanted to work with used things,” he says. “To create organically shaped objects made of many ‘cells.’” Curlers became building blocks, like molecules or coral fragments, reimagined into striking sculptural forms.

Featured Works

Two of Weinberg’s pieces, Rainbow Planet (2023) and Dark Rainbow Cells (2024), push that idea further.

“Rainbow Planet” (2023)

Rainbow Planet is a radiant orb built entirely from used curlers, self-supporting and internally connected with cable ties. “The curlers come from a wide variety of people whose heads they have been in contact with,” Weinberg explains. That diversity is mirrored in the color spectrum of the piece itself—a soft but vivid symbol of shared experience, connection, and individuality. “The structure reflects our close connection,” he says.

“Dark Rainbow Cells” (2024)

Dark Rainbow Cells, by contrast, uses flocked metal rollers in rich, shadowy tones. He describes it as denser, more mysterious. “In contrast to other curlers, they have little transparency, which leads to strong shadow formation.” The resulting piece calls to mind coral, cells, and deep-sea organisms—but also hints at something familiar and human. “Many viewers see them as cheerful and humorous,” he says. “They often evoke early memories of their mother, aunt, or grandmother with curlers in her hair.”

Seeing the Absurd, Too

Weinberg is clear-eyed about the connections he’s making between natural systems and everyday life—but he also doesn’t mind if viewers find a little humor in the work. His sculpture Zum Zweck der Locke (The Purpose of the Curl), made with 90 different curlers of 90 participants in his art project, asks playful questions about utility, nostalgia, and the absurdity of the objects we surround ourselves with.

Zooming in on petals and fruit, Weinberg magnifies not just the object but its meaning. “The size also increases the significance,” he says. “If we look at a gooseberry the size of our head, we take it more seriously than in its actual size.”

For all the precision in his work—golden ratios, 60° and 120° divisions, Fibonacci spirals—there’s also a deep appreciation for imperfection, intuition, and organic change. “Nature constantly oscillates between organic and geometric,” he says. “That’s what I try to do too.”

Explore more of Achim Weinberg’s circular worlds on his Artrepreneur profile, and see how he turns the ordinary into something wonderfully strange, thoughtful, and alive.