Go to any art museum in the world and you’ll find hundreds of visitors with cameras in hand, snapping photos of their favorite, well-known works. Many of these great pieces no longer have copyright protection yet, these institutions often sell merchandise such as posters that claim the Museum has copyright ownership. As a copyright holder, that institution would have the exclusive right to reproduce the work, make derivatives of it, publicly display it, and distribute it. Conversely, that also means the copyright holder can stop anyone else from doing those things. Take the Monet poster of The Four Trees from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, shown here. This poster includes a copyright notice: © 2010 MMA.

If the Monet is in the public domain, meaning free from copyright protection, then how can the Met Museum claim copyright on such an old work? If The Four Trees is really copyright-free, then can someone sell an image of the work? Can the Met Museum stop someone from taking a photo of the painting and selling that photo or creating posters from it? For that matter, who would hold a copyright on a photo of a copyright-free work?

To answer these questions, we have to look at what makes a work eligible for copyright and what rights a museum has over the artwork shown in its galleries.

What Types of Creative Work Can Receive Copyright Protection?

Let’s start with some basic tenets of copyright protection. First, the Copyright Act says that copyright protection is available for “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression . . . ” That’s just a fancy way of saying that the work is new and unique. It isn’t a copy or based on someone else’s work and the work has been produced onto something tangible that enables it to be perfectly reproduced and shown to others, such as a work on paper, photos from a digital camera, or a .jpg image file.

An example of art that cannot be reproduced perfectly would be performing arts like dance moves live performances or speeches. In order to reproduce those perfectly, they need to be recorded onto something tangible like a film or a recording. In that case, the recording of the performance can be perfectly reproduced but the live performance itself cannot. Because the next time the artist performed, it would not be exactly like the prior performance.

In addition, the courts have said that for a work to be copyrightable, it must have some level of creativity. Admittedly, this is somewhat subjective and there is no “bright line” from which we know must be crossed to determine the level of creativity required. However, in general, the required level of creativity is very low.

So, if a work fits these criteria; original, tangible and creative, then copyright is automatic and immediate. For example, if you take a photo of your friends with your iPhone camera, the photo is automatically copyrighted because 1) the composition of the photo such as the placement and position of your friends and the setting is unique and original; 2) the choices you made when taking the photo, such as the angle and distance is considered creative; 3) the photo is captured by the camera sensor so it is fixed in a tangible medium. All three criteria are therefore met. (note: registration with the US Copyright Office is not required but doing so has some advantages –see Why is Copyright Registration Important?).

One last point you should be aware of for this analysis: copyrights do not last forever. The Constitution states:

[The Congress shall have power] “To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” Article 1, Section 8

The definition of limited time has changed over the years making it difficult to know when work no longer has copyright protection, however, one rule you can always count on is that any work created before 1924 is in the “public domain,” meaning it has no copyright protection and is free to use in any way you like.

Is The Met’s Monet Poster Protected By Copyright?

Now that we know the basic factors for copyright eligibility, let’s use these concepts to analyze whether the Met Museum can claim copyright for the Monet poster. First, we know the poster is fixed in a tangible medium. In this case, it is the paper the poster is printed so that part is fine.

What about originality? One could argue that the Met Museum has merely reproduced Monet’s work so from that perspective it is just a copy and therefore, not original. In addition, Monet’s The Four Trees was created in 1893, and as discussed, any work created prior to 1924 is in the Public Domain. Reproducing artwork that is in the Public Domain cannot extend copyright protection; otherwise, every time a creative work had reached the end of its copyrightable life, the author could just take a picture of it to renew its copyright. The requirement for a limited time would essentially be meaningless.

If the Monet Poster is merely reproducing the Monet, then it cannot claim copyright protection.

So How Can the Met Museum Claim Copyright In The Monet Poster?

Well, the copyright isn’t in the Monet painting but in the poster itself. If the creator of work incorporates preexisting material from another creator, such as public domain or other copyrighted works, into his or her new work, the new work can receive copyright if 1) the creator disclaims the preexisting material and 2) the remaining part of the work is copyrightable (i.e. original, in a tangible medium) and has some creativity.

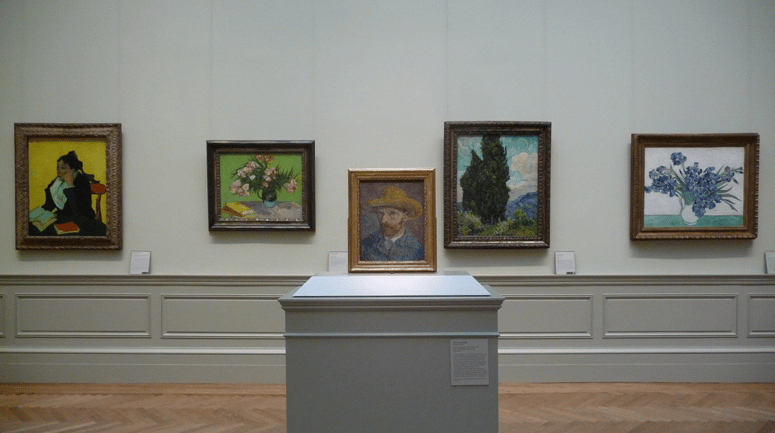

For example, the photo of Van Gogh’s Self Portrait taken at the Met Museum (shown below) is copyrightable because the Van Gogh is not the sole component of the photo. The photo includes original components such as the angle, depth of field, perspective, and distance from the work which are all creative choices. However, if the work was not in the Public Domain, let’s say an artwork by Andy Warhol, then the photo could get copyright protection after disclaiming the copyrighted elements, but couldn’t be copied, distributed, or publicly displayed without permission from the copyright holder( i.e. the Warhol Foundation.

Taking a photo that includes the surrounding location can be copyrighted.

The Monet poster is no different. Monet’s The Four Trees is not the sole element on the poster but includes text that is not haphazard but designed, even if the design is a simple one. The position of the text on the page, the font, and size, as well as the choice of color (or lack thereof), are all creative choices and are unique to this poster. So, the Met Museum is claiming copyright protection for the layout of the poster, not the Monet itself, which it would have to disclaim.

Watch Out for the Museum’s Terms of Service.

While taking a photo of a Public Domain work is free to sell from a copyright perspective, there are other legal issues to consider. One of these issues is contract law. When you buy your ticket to enter a museum, even if the museum is free to enter, there are usually Terms of Service that you agree to in exchange for entering the museum. The terms dictate behavior and rules of the museum and can be far-reaching, including expected behavior, age limits, use of certain equipment, or even what size bag you are allowed to bring into the museum.

You automatically agree to the Terms of Service when you step onto the museum grounds. An explicit agreement, acknowledgment, or even knowing where to find them is not required. The Terms of Service are unique to each museum and can vary widely, especially between private, public or government-subsidized institutions. Most will include a section related to photography.

The Met Museum’s photography policy states:

“Still photography is permitted for private, noncommercial use only in the Museum’s galleries devoted to the permanent collection. Photographs cannot be published, sold, reproduced, transferred, distributed, or otherwise commercially exploited in any manner whatsoever. Photography is not permitted in special exhibitions or areas designated as “No Photography”; works of art on loan from private collections or other institutions may not be photographed. The use of flash is prohibited at all times and in all galleries. Movie and video cameras are prohibited. Tripods are allowed Wednesday through Friday, and only with a permit issued by the Information Desk in the Great Hall. “

According to these terms, despite the copyright issues discussed earlier, selling photos taken within the museum is prohibited and overrides any issues of copyright. So even though the work is in the Public Domain and the only place to take a true photo is at the Met Museum, you would still be unable to sell the photo taken there.

While you cannot sell a photo of The Four Trees taken at the MET, that does not mean that someone cannot sell an image of The Four Trees. Nothing discussed here precludes selling a Public Domain image. The only impediment would be getting your hands on an image large enough to produce a quality poster. You could, for example, buy the Monet poster and scan or take a photo of The Four Trees only and reproduce it as a poster. Alternatively, you could find a version of The Four Trees on the internet that is large enough to reproduce. However, be careful that the site doesn’t also have its own Terms of Service with a limitation on downloaded content. (Here is a link to Monet’s The Four Trees that fits this criterion.)

So how can museums copyright paintings from old masters? As we have seen, they can’t. What they can do, though, is copyright the poster and place the copyright notice in such a way that it misleads people into thinking that they have this right.

Have you seen any museums try to assert copyright on works from the Old Masters? Let us know in the comments below!