It has become a common refrain among lawyers who represent photographers and other artists that it is important to register your work with the U.S. Copyright Office. Although registration is not required for copyright protection, it is a prerequisite to bringing an infringement lawsuit, and timely registration (within three months of publication or before an instance of infringement) is required to recover statutory damages and attorney’s fees. Because the costs associated with bringing an infringement suit can add up fast, many lawyers won’t take cases unless the infringed work has been properly registered.

The thought of registering your images might be a little daunting, especially if you’ve never done it before, but taking the time to think through some foundational considerations before you begin can simplify the process, save you time, and minimize the chance that you’ll get follow-up questions from the Copyright Office.

In the following excerpt from my book, Copyright Workflow for Photographers: Protecting, Managing, and Sharing Digital Images, I walk through some of the basics to think about before registering your work, and conclude with some suggestions about how to build routine registration practices into your everyday workflow.

Published or Unpublished Works?

The first decision you need to make is also perhaps one of the trickiest (and most frustrating) aspects of registering copyrights in photographs: whether the images have been “published” under the law. Because the requirements for registration differ slightly depending on whether you’re registering published images or are unpublished works, it’s a determination that you have to make before starting the registration process.

Copyright law defines publication as:

the distribution of copies or phonorecords of a work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending. The offering to distribute copies or phonorecords to a group of persons for purposes of further distribution, public performance, or public display, constitutes publication. A public performance or display of a work does not of itself constitute publication.

In the days of film photography, the decision was fairly straightforward: If the images hadn’t yet been distributed to anyone (say, a client or a stock photography agency), then they would be construed as “unpublished.”

But what about works posted on the Internet (say, a personal blog, or a photo-sharing site like Flickr)? On the one hand, it seems like posting images on the Internet might be considered a “distribution of copies,” so under the definition above, it would be considered a publication. But it would also be a “public display,” and the second part of the definition above explicitly excludes public display from the definition of publication.

Although there are various views throughout the copyright community, one dominant school of thought, and the one I follow personally, is that if you post an image to the Internet and encourage or allow users to make copies of the image—either electronically or by purchasing prints or products bearing the image, or something like that—the image is published.

If, however, you make it explicit that making copies is prohibited (through copyright notices or terms of use that expressly limit the user’s rights) and/or take technical steps to prevent people from making copies, then the images may be unpublished (that is, for public display only).

So, for example, if you post an image to your blog that contains a copyright statement in the footer, your images are probably not published. Similarly, if you post your images to a photo-sharing site and explicitly identify them as copyrighted (most such sites let you specify copyright parameters), then the image is likely not published. If, however, you upload an image to that same site and enable users to order prints or you select one of the Creative Commons licenses that many such sites include, then the image is probably published.

Making the right choice between “published” and “unpublished” is important because if you register your works incorrectly, the registration could be successfully challenged by your opponent in court, and you could lose your eligibility to receive statutory damages and attorney’s fees.

CAUTION! If you’re ever uncertain about whether your works are published or unpublished for purposes of copyright registration, consider speaking with an attorney to help you make a decision and determine the best course of action.

Why does publication status matter in the first place? Although the concept of “publication” might seem arcane, the distinction is important for more than just determining which form to file with the Copyright Office. In fact, it comes up in several places throughout copyright law. For example, whether a work is published or unpublished is a consideration in some fair use cases, and certain limitations on the copyright owner’s exclusive rights apply only to published works. For works made for hire, the length of copyright protection is determined by the publication date, and publication status also governs the type of deposit materials that a copyright owner is required to submit along with his or her registration (although for most photographers the rules are generally the same regardless of whether the work is published or unpublished).

Determining the Filing Type

Once you’ve determined whether the work you plan to register is published or unpublished, you can move on to figuring out which registration filing approach you’ll take. The Copyright Office offers three ways by which you can register your images:

- A single image on a single form

- A collection of unpublished images on one form

- A group of published images on one form

Note the subtle differences in descriptions: for published works, it’s called a group, and for unpublished images, it’s a collection. Although the distinction might seem trivial, it’s legally significant, because groups and collections are two separate procedures under the Copyright Office’s regulations and have slightly different requirements. The biggest practical difference between the two bulk registration options is that collections (unpublished) can be filed either online or on paper forms, whereas groups (published) can be filed only on paper forms.

The most straightforward registration application you can file is for a single published or unpublished image. You can file this kind of application online using the Copyright Office’s online registration platform, aptly called the Electronic Copyright Office (eCO) or by filing a traditional paper form known as Form VA (“VA” stands for “visual arts”). The current cost for filing an application for a single image is $55 for applications filed online and $85 for paper applications (note that Copyright Office fees change from time to time, so always be sure to visit www.copyright.gov for the latest).

The Copyright Office offers a discounted rate for what it calls a “single application,” which is an application filed online for a single work by a single author (who is also the copyright owner of the work) and that is not a work for hire. So, if you took an image and you are the sole copyright owner (as opposed to your company, or some other third party) and it is not a work made for hire, then you qualify for the single application fee, which is $35.

Of course, given the volume of images that most photographers produce, even at $35, the cost of registering every image, or even your “keepers” would probably be prohibitively high. Fortunately, the Copyright Office has created two batch-submission options that will allow you to register multiple images on one application, which I discuss next.

A collection of unpublished images.

You can file a registration application for a collection of unpublished images either online or using paper Form VA. To qualify for treatment as an unpublished collection, you must meet the following regulations of the Copyright Office:

- The collection must bear a single title that identifies the collection as a whole. The title doesn’t have to be anything fancy—it could just be “January 2015 Images,” for example.

- The copyright claimant (that’s you) is the same for all the images and for the collection as a whole.

- All the images are by the same author, or if they are by different authors, at least one of the authors must have contributed copyrightable authorship to each image.

The regulations explicitly say that although you need to complete only one form, the registration of an unpublished collection is deemed to extend to each individual copyrightable element within the collection.

CAUTION! Despite the clear language in the Copyright Office’s regulation, a number of attorneys and other advocates for photographers have taken the position that registering works as an unpublished collection is risky because there is a chance that in the event of an infringement, a court would conclude that the “collection” is a single work and that each individual photograph within the collection is worth only its prorated share of the total damages award. If this concerns you, consider consulting an attorney before filing an application for an unpublished collection, or file individual applications for each of your images.

The registration fee for a group of unpublished images is $55 for an application completed online and $85 for a paper application. There is no limit to the number of images that each unpublished collection may contain.

You cannot mix published and unpublished images together when you register using the Copyright Office’s batch submission options. You must first separate out all your unpublished images and all your published images and prepare separate applications for each group. For more on published images, see the next section.

A group of published images.

To file a registration application for a group of published photos, you must use paper Form VA. Although the Copyright Office has been experimenting with accepting group registrations using its online platform, as of now it remains a pilot project. You can find additional information about the project on the Copyright Office’s website at www.copyright.gov.

To be eligible to file an application for a group of published photographs, you must meet the following regulations of the Copyright Office:

- The copyright owner must be the same for each of the images contained in the group.

- The photographer must be the same for each image contained in the group.

- Each photograph within the group must have been published within the same calendar year.

- You must be able to identify the date on which each image within the group was published.

Just like registration for an unpublished collection, the Copyright Office construes the registration for a group of published photographs to extend to each photograph in the group.

The cost to register a group of published photographs is $65, which is slightly cheaper than a typical paper form for registration.

Registering Edited Works

Suppose you register your images right as they come off your camera as an unpublished collection. After you register, you edit a handful of images and post them online in a manner that constitutes “publication,” as discussed earlier. Do you need to register those edited versions separately?

Under copyright law, the edited versions would constitute “derivative works” of the raw images covered by the unpublished collection. Any infringement of the derivatives would likely also infringe on the underlying works (the images covered by the unpublished collection registration), so your ability to sue and obtain enhanced damages remains intact.

However, to be safe, many photographers will separately register the final versions individually, noting in the appropriate fields on the application form what makes the edited version different from the underlying raw images that were previously registered.

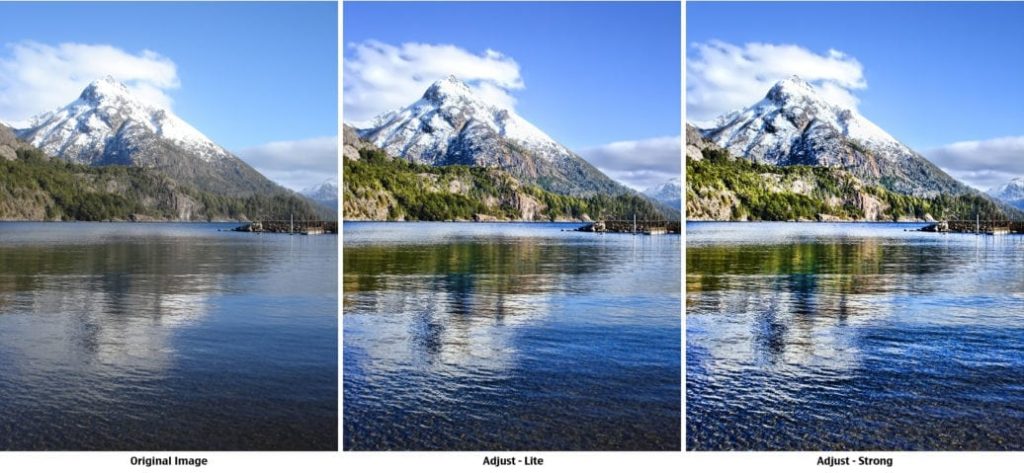

HDR with Topaz Adjust

For example, suppose a photographer takes three bracketed exposures that were registered as an unpublished collection and subsequently creates a new, tone-mapped high-dynamic-range (HDR) image based on those three images and register the new HDR image separately. The second registration would be appropriate as long as:

- There was sufficient additional authorship in the HDR image.

- The registration application properly notes that the underlying images were previously registered.

- The registration application describes the nature of the additional authorship that was added (for example, tone mapping, color correction, compositing, retouching, and so on).

Building a Routine for the Copyright Registration Process

So far, I’ve discussed the threshold question of publication status and offered some basic parameters of the three major registration options and some thoughts about registering raw images versus final, edited versions. But how does this information translate into daily practice?

My own personal practice is to register images immediately after they come off the camera, so there is no question as to whether the images are published or unpublished. I call this, somewhat uncreatively, the shoot-by-shoot approach because it requires that I file a new registration every time I come back from a shoot. This works well for me because I have a relatively modest number of shoots, but if you shoot more regularly, this approach could become prohibitively expensive.

Another approach is the periodic approach, in which you register all the images captured during a particular period of time. Many people who practice the periodic approach register every three months—once per quarter—so that any published images are always registered within three months of publication, as is required to be eligible for enhanced damages (see Chapter 1).

Depending on the volume of images you have, filing two registration applications (one for published, the other for unpublished) every registration period may work out to be less expensive than the shoot-by-shoot approach.

Finally, there is the individual image approach, which is just as it sounds: You file separate registration applications for each image instead of packaging them in batches. This works for photographers who produce a relatively low volume of images or want to register only those images that they deem commercially viable. Because individual image registrations are the cleanest from a legal perspective—there are no questions as to the effectiveness of the registration procedure (see “Is batch registration legal?”, earlier in this chapter)—some photographers have opted only to register individual images even though it’s more expensive.

Determining which approach is right for you requires a balancing of administrative convenience, legal risk, and cost. If you’re uncomfortable filing batch registrations, filing individual registrations is probably a better option, but the tradeoff is that your registration expenses will increase dramatically. If you don’t want to spend that kind of money, registering in batches is still better than not registering at all.

Only you, in consultation with your financial and legal advisors, can determine what’s most appropriate for you and your business. This post, and the book it comes from, explain the process and the law, but ultimately how you implement copyright registration and other rights management practices depends on your individual circumstances.