I first encountered Robin Antar’s pop art sculpture when searching for images of food in artwork on Artrepreneur’s global marketplace. I came across “Ballpark Frank” and thought to myself, Oh, someone is making adorable little clay figures. I thought the sculpture was the size of an actual hotdog. Then, I realized it was almost 40 inches long, and made of travertine stone. I had to know more. Who was this artist who decided the humble hot dog should be carved from the same material as the famous Trevi Fountain in Rome? The answer: Robin Antar, the first female artist exhibited at Pop International Gallery in New York City and a prolific chronicler of post-9/11 American identity in pop art and abstract sculpture — who does it all while being blind in one eye.

I started asking Antar about her pop art sculptures of food, and the more I learned about her, the more I wanted to know. The more I knew, the more I wanted to share. In this interview, Antar reveals her process of transmuting her emotions into her stone sculptures and how this helped her to grieve when death hit close to home. But don’t look here for a pity party: Antar lives life with ferocity and she is armed with a high-powered air hammer

How did you get started as an artist?

Sculpting has always been my spiritual refuge. I began carving stone in high school as a means of survival after my family moved from New Jersey to Brooklyn. I was sixteen and didn’t know anybody in my new school. The social climate as a teenager was brutal, until one of my teachers invited me to take a sculpture class. I was hooked! I did twenty sculptures in six months.

I’d work for hours in the school’s studio and then go home and work through all hours of the night in my parents’ basement. My father would come down to my studio at three in the morning to remind me to go to bed.

I would take raw stone — no model, no nothing — and just create whatever came to my mind. Whatever mood I was in, that’s the kind of piece I would do. When I expressed myself through art, what I made came out as visible, tangible expressions of my feelings.

What drew you to sculpture?

I’m very aggressive, which is why I prefer stone as my artistic medium. I tried other mediums in high school, but fell in love with stone because the work is very physical. Clay was too soft; it made me so crazy I threw it across the studio and went back to working with stone.

The physical nature of my creative process allows me to infuse each piece with all the emotions at play: joy, heartache or rage simply adds more fuel to the fire. I’ll attack a 1,500-pound block of marble with diamond blades and high-powered air hammers to chisel away at anxiety and frustration.

As an artist, when you have a feeling, or have something you want to say, it doesn’t go away after saying it once—you repeat it in different ways, in different forms, in different stones. Going through all those iterations can move your mind from despair to a transition state, and the process makes you grow stronger. Removing layer after layer of stone, I also peel away my memories, both precious and painful, carving down to where I can manage them.

Sculpture is a male-dominated field, even more so for artists working in stone. How did you, and do you, navigate that culture?

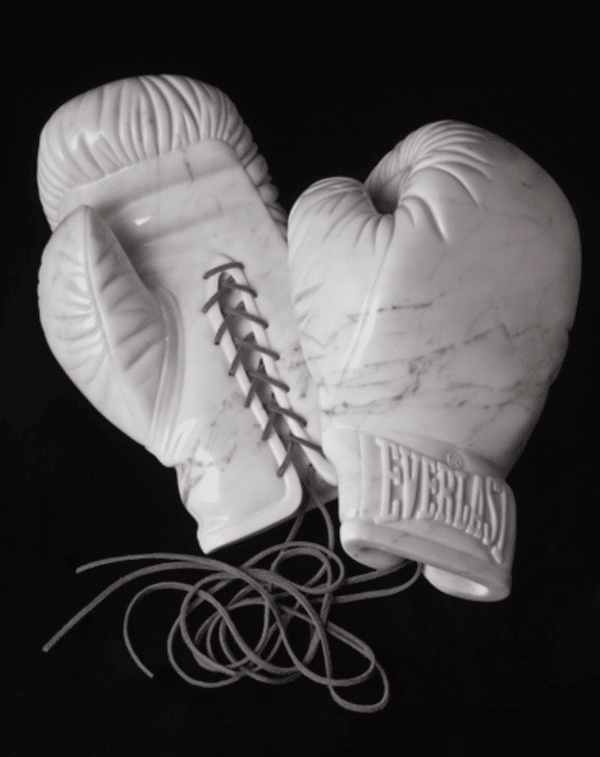

I’m aggressive in my art and I have to be equally aggressive in business to get myself noticed as a woman in the art world. That’s how I became the first female artist on the roster of Pop International Galleries in New York that represents works by Andy Warhol. I’d been bugging that gallery for years. One day I asked the owner what he wanted me to make and he said, “Boxing gloves.” I resonated with the theme since I was going through a lot in my life at the time, so I made boxing gloves. Since then, every time I’d make a new piece I would share it with the gallery, but I would only make pieces that reflect my purpose and my vision. After my acceptance at Pop, the icing on the cake was when a HuffPost writer called to interview me for an article about it.

“Win the Fight” (2010) depicts artist Robin Antar’s relationship with aggression in carrara marble.

How and why did you choose food as the subject in your artwork?

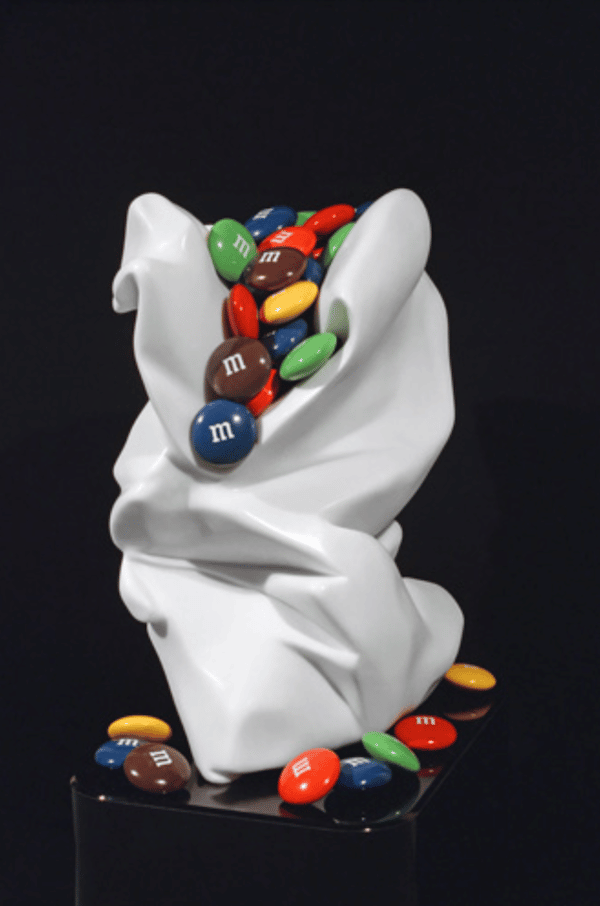

As a teen, I began carving abstract sculptures that were deeply rooted in my emotions. I explored more realistic subjects later in my career, but it was the September 11 attack on the Twin Towers in 2001 that changed everything for me, especially since my Brooklyn studio was so close to the event. It affected me deeply and made me think, “What is America? What could I carve in stone that would represent this moment in our history?” To me, America is comfort food and fun, so M&M’s spilling out of a crumpled bag became the perfect representation for America in the sculpture, North Tower 9/11.

Stone sculptures like Robin Antar’s “North Tower” (2004) represent pivotal moments in American culture.

My “Realism in Stone” series soon became a statement of faith in the future of American culture while questioning the direction our society will take.My mission is to create a visual record of American history and contemporary culture through sculpture in stone. The series explores these themes through the lens of food – comfort food in particular. What is America? Is it the all-American ballpark frank? A summer barbecue with hamburgers on the grill? Oreo cookies with a glass of milk? What do these icons of American popular culture represent today? Will they still have relevance fifty years from now? My work explores these themes through larger-than-life, hyper-realistic sculptures in stone – where a simple hot dog becomes a monument to American life and a bottle of French’s Yellow Mustard evokes memories of the classic American diner. These are moments in time that question our collective view of America.

I noticed the pop art sculptures of food you choose to create are mostly comfort food, or affordable food or condiments. What is the reason you chose to make stone sculptures of bagels, mayonnaise, and hot dogs as opposed to a standing rib roast or cake or deviled eggs?

The series presents opposing aspects of Americans’ exterior and interior lives through cultural symbols of American middle- and working-class products.

“Summer Barbecue,” for example, was inspired by a fond childhood memory of my neighbors who used to invite me over to their house for a barbecue during the summer. The food and the friendships represent the best of America.

The question of “What is America?” also prompted a sculptural exploration into my own Jewish heritage as I created a larger-than-life replica of a bagel and the famous mefuneket sandwich from Moti Rabinowitz’s Think Sweet Cafe in Brooklyn, which was featured on CBS New York.

Part of this series also includes carved stone replicas of Heinz Ketchup, Hellman’s Mayonnaise and French’s Mustard. I don’t like condiments. I don’t even have them in my house. But every restaurant you go to there’s mayonnaise and ketchup – it’s a big thing for America. I’m working from old-school classic labels to evoke a sense of nostalgia.

These works imitate form and surface in a trompe l’oeil realism that masks marble’s sensual qualities.

Robin Antar says her pop art sculptures like “realism in stone 38” (2011) are a commentary on American identity and class.

Can you talk a bit about the significance of shoes in your work?

The shoe series was created in the very beginning of my “Realism in Stone” work. I had been creating abstract work since I first put chisel to stone in 1974 until one of my sculpture students asked me to work on a realistic replica of a boot as a commission. My young son was inspired by the idea of carving from real objects and said, “Mom, why don’t you make a giant sneaker?”

As an artist with many years of practice, I was confident I could carve anything. But creating hyper-realistic pieces would be a particular challenge for me since I am blind in one eye. I don’t have depth perception, which is crucial for a sculptor, so I learned to compensate. I used a straight edge, lined it up against the object to be replicated and worked with the negative space.

After I finished the boot commission, I photographed it and sent it to Skechers, the footwear company in California. They responded within five minutes and commissioned me to create a stone replica of one of their products!

Thus began my realism work. Since then I created penny loafers, work boots and even sandals, often contacting companies for commissions. Whenever I’d walk into the studio — with the real subject next to the carved replica — I’d do a double take, wondering which one was which. That’s when I knew this realism series would be successful.

I have no problem switching from hard objects to softer ones, and back again. I’ve carved a comfortable pair of jeans (my own jeans), a denim jacket, and well-worn cowboy boots. I was featured on HGTV’s “That’s Clever” who traveled to my studio to film my boots and carving process.

“Horseback Riding Out West” is part of Robin Antar’s series on shoes.

What do your abstract sculptures represent for you, as a maker?

I still create “Expressions in Stone” sculptures: pure abstractions of personal emotions that explore teenage angst, relationships, marriage, motherhood and the challenges of life. It’s a different process than the realism series; I carve intuitively as I breathe my emotions into the grooves of my work. Stone “knots,” for example, initially represented the anxieties and difficulties of raising children and dealing with child abuse, divorce and death. My newer “knot” works reflect more universal themes of struggle, such as the current challenges of our nation.

Now I switch back and forth between realism and expression, depending on what I’m feeling about a particular event or observation.

Describe your process. What kind of tools do you use? How can you tell if a work is finished?

As a sculptor, I am drawn to the subtraction process of carving and working with grinding tools. The sculpting process is very physical, with diamond blades and high-powered air hammers used to cut and chisel the stone. The sanding process is labor-intensive and done by hand, using multiple diamond grits to achieve an exceptionally smooth finish. Different textures can also create various emotions as the surface can be chiseled, polished, rough-cut. All of these tools are my spiritual channels as I chisel away stress, anxiety, frustration or anger, which vanish as I cut into the rock, often resulting in transformation and moments of peace for myself as well as the viewer.

The stone I use in my work comes from quarries throughout the US and around the world. Most of my work is carved in marble, travertine, onyx, calcite, limestone and alabaster.

Limestone is used for work I want to color with custom stains, which allows me to match the color of the original subject. The stains are created through a special tinting process I developed forty years ago to duplicate the color of almost any product I choose to replicate for my realism pieces.

The type of stone often depends on the mood of the piece since different stones give different moods. A sculpture in honeycomb calcite from Utah – a light, airy, glass-like stone – has a completely different feeling than an opaque white stone like marble. This is why I selected honeycomb calcite for Entanglement, which I carved after reading 50 Shades of Gray. The sculptural form represents the pain of a female figure yet I purposely chose this light and airy stone to present a conflict within the piece. Honeycomb calcite is also used specifically for its natural color, such as the fries in my hamburger sculpture, Summer Barbecue.

Antar selected honeycomb calcite for “Entanglement” for its colorful qualities that evoke mood.

A finished sculpture “works” for me when I feel it has “life.” I’m not afraid to go into raw stone and “cut the line.” Whether the piece is a realistic or abstract sculpture, it’s important for the form to have vibrant movement. This is what provokes a visceral response to the work – what every artist strives for.

One of the highest compliments I received was when I submitted one of my realism pieces for copyright protection from the U.S. government. They replied that I cannot copyright my work of art because it too closely resembled the product that I chose to record in stone. The day I received that letter was one of the happiest days of my life because it confirmed the high level of realism I had achieved in my work.

Have you ever experienced creative blocks? How did you get to the other side of it?

In 2013 my youngest son, David, passed away at the age of 26 following years of addiction due to child abuse. A month after his passing, in an effort to console me, a close friend from Israel traveled to New York to spend time with me. I had recently received an invitation to participate in an exhibition in Israel but I had no intention of doing the show. I was not in the mood to go down to my studio and start rough cutting raw stone. My friend noticed the exhibition invitation and said, “You are doing this!”

So I humored her and came up with a concept of two forms, starting from the same roots, twisting away in separate directions, both bent down in sorrow. Suddenly, I could hardly wait to start cutting stone and chose a rare piece of purple alabaster I had in my studio. I began whacking at it and as I worked, I literally fell into a trance, as if I had lost touch with reality. I started creating an “expression piece” in this soft stone, chiseling away, getting into the groove. It feels so good: the mind goes into a flow state, and your air hammer becomes an extension of your hands.

My friend knew me so well: Sculpting, more than anything else, was exactly the therapy I needed to begin recovering from the worst trauma of my life:the loss of my baby boy.

Robin Antar’s “David’s Knot in Flames”, honoring her late son, is permanently installed at Zucker Hillside Hospital in New York, where he received treatment.

Is there one sculpture you are particularly proud of?

The most personal and powerful sculpture I ever created was “David’s Knot in Flames,” honoring my late son David. I selected a 1,500-pound piece of Turkish marble and worked on it at the MARBLE/marble Stone Carving Symposium in Colorado.

I started work on the sculpture just nine months after his passing, so my emotions were still very fresh. I have no idea how I had the ability to carve this piece. I don’t remember the process at all, I was in such a rage. At the end of every day, however, one of my friends at the symposium would walk by my carving site and give me a hug. I would start to cry and then stop working for the day. You can’t use these tools when you are not 100 percent stable.

I worked very quickly, considering I did not work that many hours; I cut 1,000 pounds off the stone in about sixteen work days. Considering I only used a five-inch diamond blade, that is very fast. I got most of the lines defined that first summer. I lost awareness of my motions as my hands and tools were working together, perfectly in sync. It was just the therapy I needed at that difficult time.

However, as I was carving the hole in the center of the piece for the negative space, I did not have a spotter to direct the coring bit in the correct direction, so that the drill hole will come out where you want it on the other end of the stone. I just went in and attacked it. I was angry and took it out on the stone; the stone responded in kind: my hole came out eight inches lower on the other side. I had to then re-think my idea, and made the knot open up and burst into a flame – representing David’s soul rising to heaven.

This was one of the most emotionally challenging pieces I have carved. Not in the carving itself, that part was easy; it was the feelings that went into it. Transferring emotions into rock takes sweat and work using hand-controlled tools. This is why I feel computer-driven CNC machines are good for certain things, but they cannot put human emotions into a work of art.

“David’s Knot in Flames” is permanently installed at Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, New York where my son received treatments. It now inspires the patients admitted to their behavioral health center. A tradition among patients is to touch the sculpture for good luck so they would never have to return — a testament to the power of art.

View more of Robin Antar’s work on

Artrepreneur and leave any questions you have for her in the comments!