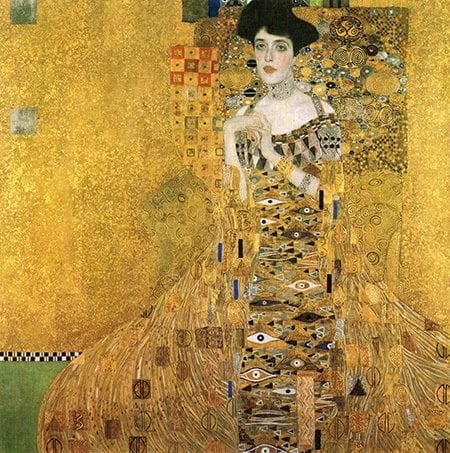

Soon after the Nazis came to power in 1933, they began the systematic appropriation of Jewish valuables, including some of the most important modern art of the early 20th century. Lately, the topic had been garnering a lot of media attention, including several books, documentaries, magazine articles and film’s like George Clooney’s Monuments Men. Joining the cannon of Nazi Art plunder films is the recently released “Woman in Gold,” the story of Maria Altmann’s eight-year struggle for the return of Gustave Klimt’s “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I.” Adele Bloch-Bauer and her husband were patrons of the arts, supporting several artists including Klimt. Adele’s husband Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, a wealthy industrialist who had made his fortune in the sugar industry, commissioned Klimt to paint the portrait of his wife. After the Nazis annexed Austria, the painting was seized by the Nazis and shortly thereafter given to the Austrian State Gallery, where it became a prized possession of the Austrian people, dubbed the Austrian “Mona Lisa” by its citizens.

Given its importance to Austrian culture, it is no wonder that Austria fought so hard to keep the work within the confines of its borders. Like many art restitution cases, the details are fascinating and the Altmann saga is no exception. However, while the film does a decent job of highlighting the strength and fortitude of Altmann, it falls short in expressing the importance that the case has had on the future of restoring Nazi plunder to its rightful owners.

On the one hand, the case shined a light on how little museums and national collections care about returning stolen Nazi plunder, as well as highlighting the unbelievable commitment required by those requesting the return of their property to see justice prevail. For Altmann and her lawyer, Randol Schoenberg, battling a foreign government over ownership of a painting was a daunting task, especially against a country trying to hold onto its most prized artistic possession; a painting synonymous with the country’s identity. While their success is a testament to Altmann and Shoenberg’s fortitude, the case had a much more long lasting result; that in cases of art restitution of Nazi plunder, national institutions cannot hide behind sovereign immunity as a means to avoid legal disputes. Sovereign immunity simply means that foreign governments cannot be forced into defending their actions in foreign courts. Until the mid-twentieth century, the sovereign immunity rule was almost absolute, however, around that time, governments and state sponsored capitalist enterprises began to broaden their roles into more than just traditional government functions, and became more involved in roles that were traditionally held by the private sector, such promoting tourism through national museums or buying art for national museums.

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I

Of course, these things had always been done to some extent but government’s hand became increasingly active, blurring the line between government and private sector transactions. Given that foreign governments were behaving like private entities, some began to feel that it was inherently unfair that these governments could not be sued in places where they were conducting business. In 1976, the United States became the first country to enshrine this idea into law with the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA). So the big question was whether these laws were retroactive, in which countries could lose their sovereign immunity for crimes committed before the laws were enacted? Altmann, having difficulties with the Austrian legal system, turned to FSIA as a way to have her Klimt returned, but was confronted with significant hurdles; ones that she managed to overcome to the benefit of herself and other victims of Nazi plunder.

The Woman in Gold Backstory

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I is the first of two portraits Gustav Klimt painted of Adele, considered an important expression of Klimt’s his “golden phase.” In 1925, Adele died of meningitis. In her will, she asked that her husband, upon his death, bequeath both portraits and several other Klimt works to the Austrian State Gallery. A decade later, the painting still hung in the Bloch-Bauer family home, when the Nazi’s invaded Austria. Less than a year earlier, Maria Bloch-Bauer, Adele and Ferdinand’s niece, married Frederick “Fritz” Altmann, and became Maria Altmann. With the invasion, Ferdinand fled to Switzerland, and his artworks and other prized possessions were confiscated. Maria remained in Austria, not wanting to leave Fritz who had been arrested and sent to the Dauchau Concentration Camp. The Nazi’s were using Fritz’ arrest to force his brother Bernhard (who had fled to France) to transfer his highly successful textile factory to the Germans, which he did. Fritz was released and he and Maria fled to the United States, eventually settling in California. (As an interesting side note; Bernhard had sent a Cashmere sweater from his factory to Maria shortly after the war. Cashmere has not been available in the United States. Maria attracted numerous buyers and became the face of Cashmere in California.) After the war, the Austrian Government kept the Bloch-Bauer collection, citing Adele’s will as having legal force, moving it to the National Gallery at the Belvedere.

Altmann had made several requests for the collection’s return, but her requests were denied citing Adele’s will. However, after Austria passed a law forcing greater Government transparency regarding Nazi looted art, a reporter discovered that Adele had not authority as she was not the purchaser, and that Ferdinand had never donated the collection. That suggested the collection remained the property of the Block-Bauer family. Altmann attempted to negotiate a deal for the collections’ return, even allowing the portrait to remain in Austria’s possession, however, a deal couldn’t be finalized. Altmann was forced to sue the Austrian Government through the Austrian courts. Unbelievable, the filing fee for initiating a lawsuit in Austria was not a flat transaction fee, but a percentage of the potentially recoverable amount. The Portrait was valued at $135 million, so Altmann’s filing fee should she want to sue the Austrian Government was $1.5 million; an amount that Altmann could not afford. As a result, she turned to the U.S. Courts, using the innovative approach of invoking the “expropriation exception” of the FSIA, as a means bringing the Austrian Government to court in the U.S. However, Altmann had two major hurdles to overcome in order to deny Austria sovereign immunity.

Altmann Turns to the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II

Under the FSIA, foreign states are presumed to be immune from the jurisdiction of US courts and from liability in US lawsuits unless property was taken in violation of international law, and fell within one of several exceptions. The “expropriation exception,” invoked by Altmann, allows a foreign state to be sued over a property located in the foreign state and the property holder engaged in a commercial activity in the United States. So first, Altmann needed to show that the National Gallery engaged in commercial activity in the United States. The Supreme Court defines commercial activity this way:

[T]he issue is whether the particular actions that the foreign state performs (whatever the motive behind them) are the type of actions by which a private party engages in “trade and traffic or commerce” …. (See Republic of Argentina v. Weltover, Inc., 504 U.S. 607, 614, 112 S. Ct. 2160 (1992).)

Foreign states, their agencies, and other state-owned enterprises are often engaged in transnational commercial activities in foreign countries, such as energy exploration, mining, banking, maritime and aerial transportation, and tourism, to name just a few. In this case, the court said that marketing of art exhibitions, including the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, and disseminating publications related to those exhibitions within in the United States were commercial activities, satisfied the commercial activity requirement.

Having overcome that hurdle, the threshold question was whether the FSIA applied retroactively, that is, to events before its passage. Traditionally, when someone commits a legal act, they cannot be retroactively punished for something they did before that act became illegal. Imagine someone drinking alcohol before Prohibition, and then being punished for that act of drinking after Prohibition came into effect. Most people assumed that there was little chance that the court would punish Austria for something that happened in 1938 by another country, and that the case would be dismissed before it even got started. But Altmann and Schoenberg pursued an interesting line of reasoning: the Government had claimed it received the painting as a donation by Ferdinand, which was shown not to be true. The Austrian government had, in fact, been aware that the Klimt had been plundered and as such, the Austrian government should have no expectation that the owner’s would want the painting returned. Altmann had made those requests several times. As well, the Court cited the fact that Altmann was unable to take action in Austrian courts due to the burdensome court costs, relegated the action to the only court that had an immunity statute. The Supreme Court agreed, and in 2004, over the objection of the United States, ruled that Austria was not immune from suit, and that the case could proceed. The result is that Nazi plunder held by Foreign Governments are not immune to court action in the United States if the plaintiff can show that there is some for of commercial activity in the U.S, which isn’t difficult given the transnational nature of commerce today.

That certainly makes it easier for victims to see restitution of their works, if they are being held by government institutions, however, the true difficulty in cases like these is usually the lack of proof that any given familial descendent were the original owners. Few records survive. Those Jews who survived the concentration camps, or others who fled earlier in the war, rarely had the luxury of taking records. In the Altmann case, records in the form of Adele’s will were available, since she had died in 1925, but for many other families, they have little more than word of mouth from a family member.

After losing its immunity, Austria expressed willingness to arbitrate the claim rather than get involved in a long out battle that it was not likely to win. This was a huge risk for Altmann, because an arbitration result cannot be appealed, and she would have to abide by the ruling, waiving her right to sue in the U.S. courts, which she had just won the right to use. But she agreed to arbitrate, and she won.

___________________

Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds

Yet, after all the time and effort, and despite the personal importance that Altmann placed on her Aunt’s portrait, soon after Altmann received the painting, she sold it for $135 million to Ronald Lauder, the billionaire art collector, who placed it in his New York art gallery, the Neue Galerie. Four other works by Klimt, the second portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer and three landscapes, were later auctioned off for nearly $193 million, bringing the total for Altmann and some close relatives to $326 million.

Altmann’s efforts were admirable, and will have a long lasting effects on future Nazi plunder cases and probably other cases involving sovereign immunity. At the very least, it will make foreign states think twice when receiving works without the proper provenance. It may already be having an effect. In November 2014, the Swiss Museum housing the Swiss Art Collection, Kunstmuseum Bern, agreed to receive the 1400 works found in the apartment of Cornelius Gurlitt, son of a Nazi Art Dealer (Gurlitt died May 6, 2014); many of which may be Nazi plunder. However, the Bern has decided that they will only take possession of works in the collection whose provenance is unproblematic