Perhaps one of the most basic features of copyright law is the distinction between an idea and a particular expression of that idea. The concept is crucial to our understanding of copyright because ideas themselves are not protectable under copyright, while the expression or execution of a particular idea typically is. Referred to in copyright circles as the “idea-expression dichotomy” or the “idea-expression divide,” the Supreme Court has observed that the fundamental principle strikes “a definitional balance between the First Amendment and the Copyright Act by permitting the free communication of facts while still protecting an author’s expression.” Harper & Row Publishers., Inc. v. Nation Enterprises., 471 U.S. 539, 556 (1985) (quoting Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises., 723 F.2d 195, 203 (2d Cir. 1983)).

We can think of the idea-expression dichotomy, then, as a way of balancing the exclusive rights of authors granted by copyright law with the free speech rights of the general public protected by the First Amendment. If ideas were protectable, it would permit every author to effectively withdraw them from the pool of ideas available to other creative professionals. Taken to its logical extreme, the world would soon run out of ideas and stifle speech with it. The idea-expression dichotomy is intended to ensure that doesn’t happen while also encouraging people to develop new creative ways of expressing ideas.

Why you can’t copyright an idea: Case Law

Today the idea-expression dichotomy is described explicitly in Title 17 of the U.S. Code (where most copyright law lives), Section 120(b) of which provides that “[i]n no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.” But the doctrine originated well before Congress had even contemplated the Copyright Act of 1976.

One of the earliest idea-expression cases dates back to 1879, when the Supreme Court considered the case of Charles Selden, the author of Selden’s Condensed Ledger, a book that described and facilitated a unique way of bookkeeping. W.C.M. Baker, the auditor of Greene County, Ohio, published his own book on accounting that drew significantly on Selden’s method. Selden sued Baker for copyright infringement and initially prevailed, but the Supreme Court reversed the lower court, holding that although Selden had a copyright interest in his book, “[t]he copyright of a book on book-keeping cannot secure the exclusive right to make, sell, and use account-books prepared upon the plan set forth in such book.” Baker v. Selden, 101 U.S. 99, 104 (1879). Put more succinctly, “[t]he description of the [method] in a book, though entitled to the benefit of copyright, lays no foundation for an exclusive claim to the art itself. The object of the one is the explanation; the object of the other uses.” Id. at 105.

Baker v. Selden also articulated another principle of copyright law, closely related to the idea-expression dichotomy, often referred to as the “merger doctrine.” The merger doctrine stands for the proposition that in cases where there is only one way, or a small handful of ways, to express a particular idea, not even the expression is protectable. In other words, the idea and the expression are said to “merge” such that protecting the expression would effectively be the same as protecting the idea.

The idea-expression dichotomy and the related merger doctrine are principles that are conceptually quite simple but can become difficult to apply, particularly because it is sometimes difficult to identify the line between idea and expression. That’s perhaps most true in the case of artistic works, where a concept or idea may take on dozens of different manifestations. How can we tell whether a particular work copies a specific, copyrighted expression (and is thus infringing) versus merely representing the idea represented in a particular work?

As Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart once quipped about pornography — “I know it when I see it” — sometimes the only way to get a sense of the distinction is to look at some examples.

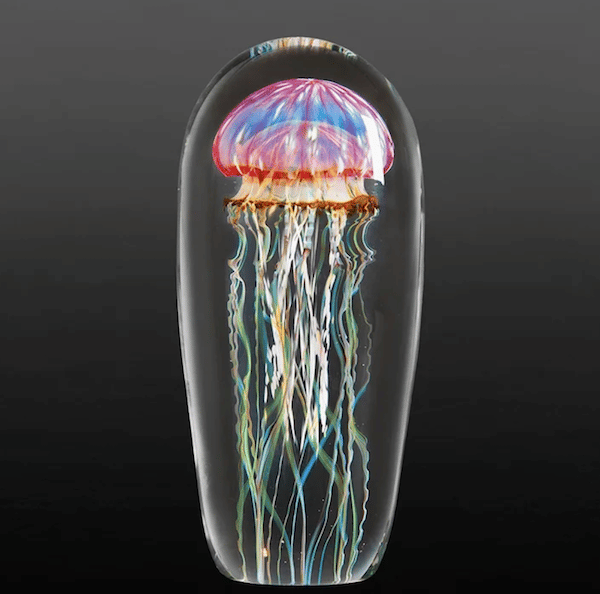

Your Glass Jellyfish Looks Just Like My Glass Jellyfish!

Following a period of artistic exploration in the late 1980s, California-based glass artist Richard Satava began producing and selling glass-in-glass jellyfish sculptures, which Satava described as “vertically oriented, colorful, fanciful jellyfish with tendril-like tentacles and a rounded bell encased in an outer layer of rounded glass that is bulbous at the top and tapering toward the bottom to form roughly a bullet shape, with the jellyfish portion of the sculpture filling almost the entire volume of the outer, clear glass shroud.” Satava v. Lowry, 323 F3d 805, 807 (2003). Satava sold his sculptures through galleries and gift shops throughout the United States.

Richard Satava could not stop other artists from creating glass jellyfish.

Enter fellow glass artist Christopher Lowry from Hawaii. Mr. Lowry also makes glass-in-glass jellyfish sculptures that, said Satava, looked suspiciously similar to his sculptures. Like Satava, Lowry sells his works through gift shops and galleries, and Lowry “admits he examined a Satava jellyfish sculpture that a customer brought him for repair in 1997.” Id. at 809.

Typically, when a copyright plaintiff shows a defendant had previously seen the allegedly infringed work and that allegedly infringing work looks substantially similar to it, it’s a slam-dunk win for the plaintiff.

But here, the court looked at the underlying ideas embodied in each of the works at issue: glass-in-glass jellyfish sculptures. The court explained that although Satava had made a number of creative contributions to the sculptures that warranted copyright protection, he “may not prevent others from copying aspects of his sculptures resulting from either jellyfish physiology or from their depiction in the glass-in-glass medium.” Id. at 811. The court went on to explain that:

“Satava may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish with tendril-like tentacles or rounded bells because many jellyfish possess those body parts. He may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish in bright colors, because many jellyfish are brightly colored. He may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish swimming vertically because jellyfish swim vertically in nature and often are depicted swimming vertically.” Id.

The court was careful to point out that it did not mean to suggest that “realistic depictions of live animals cannot be protected by copyright.” Id. at 812. But it did note that the window of protection is narrow. “Nature gives us ideas of animals in their natural surroundings: an eagle with talons extended to snatch a mouse; a grizzly bear clutching a salmon between its teeth; a butterfly emerging from its cocoon; a wolf howling at the full moon; a jellyfish swimming through tropical waters. These ideas, first expressed by nature, are the common heritage of humankind, and no artist may use copyright law to prevent others from depicting them.” Id. at 812-13.

The court found in Lowry’s favor, and today both artists continue to sell their glass-in-glass jellyfish sculptures (see Chris Lowry’s website; Richard Satava’s website).

Your Jump Shot Logo Looks Just Like Michael Jordan!

You don’t need to be a sports fan to know that the Nike “Jumpman” logo used on its Air Jordan line of products is among the most iconic trademarks of modern times. The logo is a silhouette of Michael Jordan’s pose in a famous photo of him that was taken in 1984 by noted photographer Jacobus Rentmeester. Nike licensed the photo, ostensibly only for internal display use, around the time that it was developing plans to partner with Jordan for a line of athletic shoes. Nike subsequently hired its own photographer to create a new image of Jordan, one “obviously inspired by Rentmeester’s” photograph, but with a number of modifications, including the clearly visible Chicago skyline. Rentmeester v. Nike, 883 F.3d 1111, 1116 (9th Cir. 2018). Notwithstanding a brief legal scuffle between Rentmeester and Nike in the mid-1980s, Nike continued to use the photo, including creating the famous “Jumpman” logo that now reigns supreme in the academic apparel industry.

Rentmeester sued Nike in 2015 alleging that the Nike photo and the Jumpman logo infringe his copyright in the 1984 image.

Jacobus Rentmeester said his photo was the basis for the Nike “Jumpman” logo, but he could not stop Nike from using it because the idea of a basketball player jumping is not protectable by copyright.

Although the court acknowledged that the photographs are “undeniably similar in the subject matter they depict” — Michael Jordan in a particular ballet-inspired jumping pose — “Rentmeester’s copyright does not confer a monopoly on that general ‘idea’ or ‘concept; he cannot prohibit other photographers from taking their own photos” of Jordan in the same pose. Rentmeester, 883 F.3 at 1121. The court recognized that perhaps the outcome would be different if Nike’s photographer had copied the details of the pose as expressed in Rentmeester’s picture, but “he borrowed only the general idea or concept embodied in the photo.” Id. “In Rentmeester’s photo, Jordan’s bent limbs combine with the background and foreground elements to convey mainly a sense of horizontal (forward) propulsion, while in the Nike photo, Jordan’s completely straight limbs combine with the other elements to convey mainly a sense of vertical propulsion,” id. at 1121-22, leading the court to conclude that “[w]hile the photos embody a similar idea or concept, they express it in different ways.” Id.

The court went on to compare other aspects of the images, including the outdoor setting, the positioning of the basketball hoop, the angle of the photography, and the overall arrangement of the elements, ultimately concluding that the two photos share only “general ideas or concepts: Michael Jordan attempting to dunk inspired by [a ballet pose]; an outdoor setting stripped of most of the traditional trappings of baseball; a camera angle that captures the subject silhouetted against the sky. Rentmeester cannot claim an exclusive right to ideas or concepts at that level of generality, even in combination. Permitting him to claim such a right would withdraw those ideas or concepts from the ‘stock of materials available to other artists, thereby thwarting copyright’s ‘fundamental objective’ of ‘foster[ing]’ creativity.” Id. at 1123 (internal citations omitted) (alterations in original).

Thus, the court ultimately concluded that neither the photo nor the logo infringes because they copied only unprotectable elements — the ideas and concepts — of Rentmeester’s image.

Copyright Protection is Limited

Strictly speaking, the idea-expression dichotomy limits the scope of copyright protection afforded to authors. In the abstract, that sounds antithetical to the interests of artists, but in reality, the doctrine protects artists by ensuring there is a diverse and robust body of ideas from which to draw inspiration. Perhaps the Setava court said it best:

We do not mean to short-change the legitimate need of creative artists to protect their original works. After all, copyright law achieves its high purpose of enriching our culture by giving artists a financial incentive to create. But we must be careful in copyright cases not to cheat the public domain. Only by vigorously policing the line between idea and expression can we ensure that artists receive the due reward for their original creations and that proper latitude is granted to other artists to make use of ideas that properly belong to us all. 323 F.3d at 813.

What do you think about the idea-expression dichotomy? Let us know in the comments section below.