(Updated) When we purchase an item, like a blender, a car, or a really cool toboggan for Snowmageddon races, we gain full ownership rights. This means we have the freedom to use it, modify it, dismantle it, or even discard it as we see fit. The same isn’t true when buying an artistic work, whether it’s a physical piece like a painting or a digital creation like a company logo. The buyer doesn’t receive the full set of rights. Instead, the ownership is shared, with some rights going to the buyer while others are retained by the work’s creator or copyright holder.

The concept that we can buy something without owning it entirely challenges our usual understanding of purchases, with most people assuming that acquiring an artistic work is the same as buying any other product. On top of that, the rights granted to the buyer or retained by the creator can differ depending on the type of artistic work involved. This lack of understanding has often led to disagreements between buyers and creators and, in some cases, costly legal disputes over what each party believes they own.

Setting the Stage: Hypothetical Scenarios to Analyze Ownership Rights of Artistic Works

How does a creator or buyer know what rights they have when an artistic work is purchased? While we can’t review every possible situation (that’s why we have intellectual property lawyers, after all), there are a few hypothetical scenarios that can help map out some of the more common boundaries of ownership rights.

- A wealthy executive purchases an oil painting from a living artist to be the centerpiece of his private library. After hanging the work, he feels he may have made a mistake in purchasing the painting but thinks that if he cuts it into three smaller pieces, it might look better in the room.

- After some negative reaction to his idea, the executive instead decides it would be better to sell it and consigns it to a reputable gallery for sale.

- Before the gallery takes possession of the oil painting, a major fashion magazine rents the executive’s home for a photo shoot. The photographer uses the private library as the main setting, and the oil painting is shown in the background of several photos, which the magazine publishes in its next issue.

The purchaser in each of these scenarios may be infringing on the rights of the artist or creator/copyright holder. Let’s look at each scenario and see what the purchaser may have done wrong and whether there are any defenses to get them out of trouble.

Scenario 1: VARA and the Alteration or Destruction of Visual Art

In our first scenario, our wealthy executive buys an oil painting, which he wants to cut into three sections to hang separately. Can he do this?

Until 1990, there would be little question. Nothing in the Copyright Act prohibited the purchaser of a physical, artistic work from altering it, as long as the alteration didn’t infringe on the artist’s copyright. The purchaser could even destroy the work.

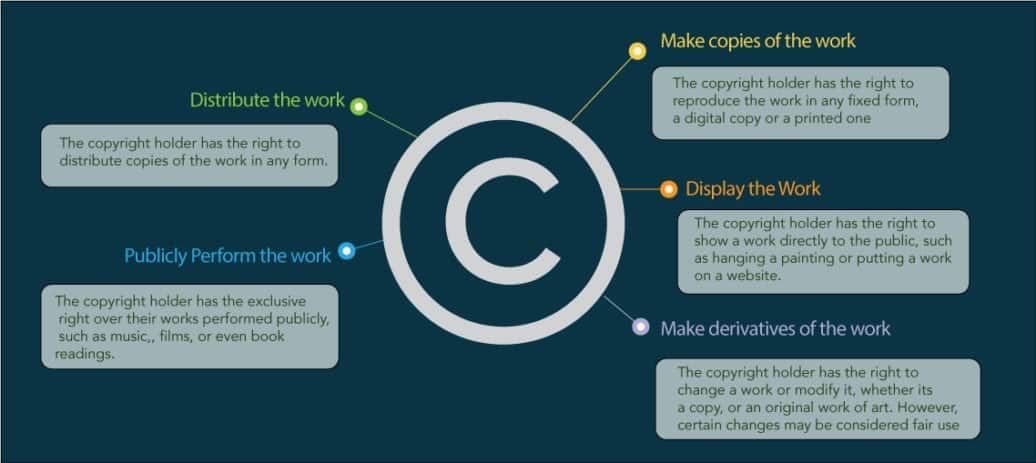

However, the ability to alter the work only applied to physical work, not the image itself. Under Copyright Law, a copyright holder has the exclusive right to:

So, let’s say someone copies an illustration they got off the web and then alters it and uses it on a brochure or a website; that would be considered a derivative work and would violate the artist’s rights. Physical work is different, though. A purchaser could paint changes onto the work or, as described in our scenario, cut it up into smaller pieces; they couldn’t copy that and distribute it because that would violate the artist’s copyright.

Many countries around the world, however, created laws that prevented the alteration and destruction of artistic works, immortalized in the Berne Convention, the international copyright treaty that the United States did not initially sign onto. Moral rights gave the creator control of the eventual fate of an artistic work, along with protecting the artist’s reputation. Moral rights included the right to receive credit for work, prevent physical work from being altered without permission, control over how the physical work is displayed, and also receive resale royalties.

After the United States signed onto the Berne Convention, Congress enacted the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990 (VARA) to better comply with the moral rights provisions. However, VARA is a bit more limited than most other countries. It grants two rights to authors of visual works:

- “The right to prevent intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification of the work that would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation” and

- The right to prevent the destruction of a work of “recognized stature.”

Note the difference between these two conditions. In the first condition, the mutilation or intentional distortion must be “prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation.” The reputational consequences must be proven by the artist, and any damages awarded would be based on the effect on the artist’s reputation. Otherwise, alterations are allowed. Destruction, on the other hand, does not require harm to the creator’s reputation. However, the work must be of a “recognized stature.” These requirements can be very subjective and hard to prove, which is one of the reasons very few VARA cases have made it through the courts.

The most prominent case involved graffiti artists at 5points in Long Island City, New York. Artists were given permission to adorn the walls of an abandoned building with art. Later, the owner of the building wanted to sell it to a developer and remove the art. Despite the protests and pending legal action from the artists, the building owner destroyed all the artwork. After a decade of legal action, the artists were awarded $6.7 million in damages. For more on the 5Pointz case, see Are Graffiti Artists Master Craftsmen or Just Audacious Vandals?

Artists at 5Pointz won $6.75 million in damages for the destruction of their work.

VARA has limitations, as well. It applies only to a “work of visual art,” which the statute designates as paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures, and photographs of recognized stature existing in a single copy or a limited edition of 200 signed and numbered copies or fewer. Photographs must have been taken for exhibition purposes only. Posters, maps, globes, motion pictures, electronic publications, and applied art are explicitly excluded from VARA protection. Finally, for works created on or after 1990, protection expires with the death of the author, but works created before VARA was enacted receive VARA protection until the copyright ends, which is the life of the author plus 70 years. Also, VARA rights cannot be transferred but can be waived if the author expressly agrees to waiver in a signed written agreement.

So, given these rules, can the Executive in our scenario cut up the oil painting into three pieces if the artist doesn’t want him to do so? Well, the painting is a work of visual art created recently, and the creator is still alive, so the situation does fall within VARA. But does it fulfill one of the two prongs? In order for the artist to prevent the executive’s action, he would have to show that the mutilation harmed his reputation. That is not easy to do in this case. It is not as if the executive wrote derogatory remarks about the artist all over the painting. Alternatively, the artist could claim that the alteration is, in fact, the destruction of the work. He would then need to show that the work was of significant stature. If the artist is famous, that would be fairly easy. The stature question becomes murkier, though, if the artist is only mildly well-known in certain circles or geographic locations. So, the artist, in this case, has a good shot at protecting the work, but it isn’t a sure thing.

Scenario 2: Inherent Rights in Buying Visual Art

The executive has decided not to alter the painting but instead resell it at a gallery. Does the Executive have any limitations as to how, where, or with whom he sells the work? Does the gallery have any limitations?

Unlike many other countries, VARA only provided limited moral rights. An artist cannot decide where or to whom a painting is resold. However, artists do have the right of attribution under VARA, which allows them to claim or deny that he or she is the creator. If the creator doesn’t like where the work is being shown, the artist can keep the seller from using the artist’s name when referencing the work but can’t stop where it is being sold, who can buy it, or where it is privately displayed.

What rights do each of the parties have in reselling a work? The artist holds the copyright and, thus, the exclusive rights that go with it, as mentioned earlier. The copyright holder can keep those rights or transfer them to another person or entity for whatever duration the copyright holder desires. Those rights are generally transferred through contracts or licensing agreements, which detail exactly which rights are being transferred, who receives them, and how long they last. A good contract should include sufficient detail regarding the boundaries of the rights being conveyed to limit any misunderstanding that might lead to a lawsuit.

What is often harder to determine are the boundaries of inherent rights, which are those rights needed in order to fulfill the terms of the agreement but aren’t specifically stated.

Artist AholSniffsGlue settled a copyright infringement case with American Eagle for using his work without permission in the background of photos used in the company’s ad campaign.

To illustrate this point, let’s look at our scenario. When the executive bought the oil painting, he had the inherent right to display the work publicly. That’s why he bought it. He didn’t need that right to be transferred in a contract or invoice. He wasn’t expected to hide it where nobody could see it. He bought it to display it. He cannot make copies of it or distribute those copies to the public. That right is exclusive to the artist. If the Executive made T-shirts with the work emblazoned on them or took a photo of the painting to put on his company website without permission, that would be a copyright infringement.

However, the Executive has the right to resell the work. At that point, he gains additional rights that are not expressly given to him by the artist but are required in order to make the sale. He can make copies of the work and distribute the copies for the purposes of helping to market the sale to the public, such as creating postcards advertising the sale. The Executive can also convey both his expressed and inherent rights to the gallery so they can sell the work for him.

How extensive are the inherent rights? The answer to that question is case-specific, and without providing those rights in a contract, determining the boundaries can often be difficult.

For example, can the seller take a high-resolution image and place it on the web, where it can easily be copied? The artist can make a case that a high-resolution image is not necessary to help make the sale, but the seller may counter that being able to zoom in on the work to see details of brush strokes can help a buyer assess quality before deciding to see the work in person.

The gallery can copy and display the work so it can make the sale, but can the gallery keep the work on its website after the sale takes place? Can the gallery make copies of the work in their promotional materials, showing it as a sold work? If the normal industry practice is being able to show the painting on its website as a sold work, then that use would probably be acceptable. However, if the gallery wanted to do more than that, for example, use it on a promotional brochure, that may be a different story.

The point here is that there are certain inherent rights that are straightforward and do not need to be formally transferred, but others aren’t so clear. Artists should consider the acceptable uses and list them and the non-acceptable uses in the purchase agreement so the buyer knows exactly what can be done with the work. The less ambiguity there is, the less likely that the buyer will use the work in an unacceptable way.

Scenario 3: Copyright Risks in Artistic Work Reproduction

Let’s look at the next scenario: before the painting departs for the gallery, the Executive’s house is used for a Magazine’s fashion shoot. The photographer takes photos of a model in the library, capturing the oil painting in the background.

When the Executive bought the painting, he was certainly given the right to display it. He also has the right to make copies for personal use. For example, the Executive takes a photo of his library with the painting on the wall. He is not required to remove the painting first. In that same vein, let’s say he is selling the house; he would not be required to remove the painting before taking the photos.

He has the inherent right to copy and display the painting for the sole purpose of selling his house. However, the executive generally doesn’t have the right to take photos of the room where the painting is prominently displayed, make copies of those photos, and distribute them commercially unless the copying relates to selling his house. He doesn’t have the right to publish those photos in a magazine or give the magazine permission to make copies and display the photos on its pages.

Let’s flush out the scenario a bit further. Let’s say the Executive mistakingly believes that since he is the owner of the artistic work, he can allow the photographer to show the painting in the background of the model photos. The magazine asks the Executive if he has the rights to the painting, and he tells them that he does and signs an agreement to that effect. The Magazine prints the photos in its next issue and distributes the magazine to the public. At that point, the magazine was infringing on the artist’s rights.

As a result, the artist is suing the magazine for infringement and demanding a licensing fee and damages. The magazine says that it did not intend to infringe and that they have an agreement with the Executive that says it can publish the photos. Therefore, they are not at fault, and the magazine should sue the Executive instead. Unfortunately for the Magazine, that reason isn’t valid.

Copyright law is strict liability, meaning it is a no-fault law. The intent or any other reasons for why they infringed do not matter. The magazine distributed a copy of the painting without permission from the copyright holder, so the magazine is infringing. Even though the Magazine thought it had permission, it is still liable. The Executive is potentially liable as well for giving permission to copyright the material even though he is not the one who copied and distributed the work.

The Executive may also be liable to the Magazine for false statements, but those laws can vary by state. The magazine should have had an agreement with the Executive for the use of his space. That agreement should include an indemnification clause just for these types of situations. A typical indemnification clause would be:

Indemnification: You agree to indemnify and hold harmless the Magazine, its affiliates, officers, agents, and employees from and against any claims, damages, liabilities, costs, and expenses, including reasonable attorneys’ fees, arising out of or in connection with the use of the Executive’s property for the Magazine’s photo shoot. This includes but is not limited to, any infringement of intellectual property rights or other rights of third parties related to items, artworks, or any other property displayed within the premises during the photo shoot.

Regardless of whether there is a formal indemnification clause, the recourse for the magazine is to sue the Executive for whatever damages and legal fees they expend in the lawsuit.

Depending upon how the painting is presented in the photos, there is also a possibility that the magazine could claim “fair use,” which is an exception to the exclusive rights of the copyright holder. (Fair use is a complex topic, which can be read in more detail in the article, Understanding Fair Use with a Star Trek and Dr. Seuss Mashup“)

_____________

The ownership of an artistic work encompasses a complex web of rights and responsibilities. These scenarios illustrate the nuanced differences between owning a physical item and owning an artistic creation. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for both creators and buyers to navigate the legal landscape effectively. By being aware of the specific rights retained and transferred in the purchase of artistic work, both parties can avoid misunderstandings and potential legal disputes, ensuring respect for the creator’s rights and the buyer’s intentions.

Did this exploration of artistic work ownership spark any thoughts or personal experiences? Join the conversation in the comments below.