It is a common misperception that you cannot copyright a building design. That is probably because, before 1990, there wasn’t much protection for building designs. At that time, anyone could reproduce buildings that looked identical to those created by others, as long as they didn’t actually use copied drawings to build them. With the passage of the Architectural Works Copyright Protection Act in 1990, architects got a much greater level of protection, being able to register completed buildings as well as drawings.

According to the Act,”[The design of a building as embodied in any tangible medium expression, including a building, architectural plans, or drawings. The work includes the overall form as well as the arrangement and composition of spaces and elements in the design, but does not include individual standard features.” Protection extends to the overall form as well as the arrangement and composition of spaces and elements in the design but does not include individual standard features or design elements that are functionally required.

The following building designs can be considered for registration:

- Designs created on or after December 1, 1990

- Designs that were created in unpublished plans or drawings but not constructed as of December 1, 1990, but were constructed before January 1, 2003

The following building designs cannot be registered:

- Designs that were constructed, or whose plans or drawings were published, before December 1, 1990

- Designs that were unconstructed and created in unpublished plans or drawings on December 1, 1990, and were not constructed on or before December 31, 2002

- Structures other than buildings, such as bridges, cloverleaves, dams, walkways, tents, recreational vehicles, mobile homes, and boats

- Standard configurations of spaces and individual standard features, such as windows, doors, and other staple building components, as well as functional elements whose design or placement is dictated by utilitarian concerns

If your design can avail itself of Copyright, that protection is automatic upon creation of the work. However, the same misconceptions that we see among visual artists also abound in the architecture world. For one, while most architects add a © notice to their architectural drawings, the © notice is not required and is not considered a ”registration.” You do have copyright in the work, but without registration with the Copyright Office, you will not receive certain benefits of copyright.

For example, if your work is registered with the Copyright Office prior to an infringement or within three months of its publication, you may be eligible to receive statutory damages and payment of your legal fees should you prevail. Statutory damages allow up to $30,000 per infringement or if the infringement is willful, up to $150,000. Alternatively, you can choose to receive “actual damages”, which may be greater as the copyright holder may be entitled to a percentage of the profits that the infringer received from the infringement. (Note that if you are not eligible to receive statutory damages, you are still eligible to receive actual damages although attorneys fees are only awarded in limited circumstances). With the high prices afforded building or new home sales, statutory damages may be lower than the profit percentage. However, with those higher monetary awards may also come higher legal fees, which will be paid for if the work is registered. Of course, every case is different, but since registration fees are a mere $35, there is little downside. (For more on benefits of registration, see this article)

If your work is registered with the Copyright Office prior to an infringement or within three months of its publication, you may be eligible to receive statutory damages.

Another misconception involves copyright ownership. Many clients of custom buildings believe that since they paid for the plans, they are the copyright holder. This is not necessarily true. Copyright generally remains with the creator. However, under certain circumstances, copyright may not be held by the work’s creator. This concept is known as a “work made for hire.” For example, copyright in an employee’s work created within the scope of his or her employment is generally held by the employer, not the employee. On the other hand, an independent contractor generally holds the copyright in his or her work, while the hiring company, such as an architectural firm, only receives a license to use the work. However, for certain categories of work where there is a written agreement, the employer may hold the copyright, not the independent contractor. (For details on “work made for hire” requirements, see this circular provided by the U.S Copyright Office.)

Copyright protection can lead to large damage awards for the copyright holder. Several years ago, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit upheld a $3.2 million award for Kipp Flores Architects, a residential design firm in Austin TX against Hallmark Design Homes. The ruling is “one of the largest awards on record in an architectural copyright dispute,” according to a Kipp Flores press release.

In another Texas case, a federal district court in Houston awarded Hewlett Custom Design Homes $1.3 million against Frontier Custom Builders. Frontier constructed and marketed 19 houses of Hewlett’s copyrighted designs. That award was based on the profits Frontier earned from the sale of the 19 houses. The court also ordered Frontier to destroy the infringing materials in the firm’s possession.

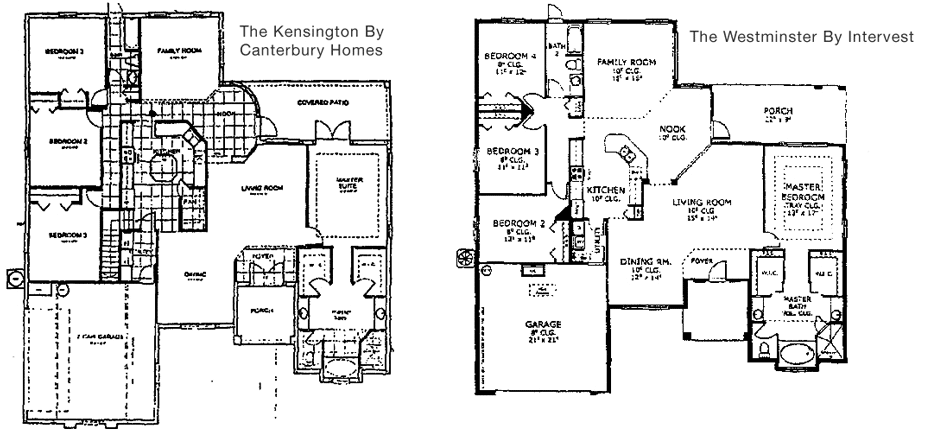

Unfortunately, proving infringement isn’t always easy, and can be a long-drawn-out affair. In an important 2008 Florida case, Intervest Construction, Inc. v. Canterbury Estate Homes, Inc., the Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit agreed with the lower district court that the two designs seen below were not “substantially similar” and therefore not infringing. According to the court, “When courts have dealt with copyright infringement claims involving creative types of works, “substantial similarity” has been defined as existing “where an average lay observer would recognize the alleged copy as having been appropriated from the copyrighted work.” How the court came to its conclusion that the Canterbury home was not infringing illustrates the difficulties in architectural infringement cases.

First, while Intervest was suing over its copyright in the “architectural work;” the design of the building, the court’s analysis did not include any elevations or section drawing of the building, or any three-dimensional architectural illustration. The court’s evaluation was based solely on their floor plans.

Second, the court stated that “the definition of an architectural work closely parallels that of a “compilation” under the statute, that is: “[A] work formed by the collection and assembling of preexisting materials or of data that are selected, coordinated, or arranged in such a way that the resulting work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship.” To understand the idea of a compilation, think about an anthology of the year’s best short stories. There is a copyright in the book as a whole, but the author does not hold copyright in the short stories themselves, which are written by multiple individuals, each of which has copyright for their story. Unfortunately, compilations are the lowest on the hierarchy of copyright protection. The court in Intervest explained it this way: “An example of a compilation is [the floor plans at issue in this case.] The [Copyright] Act has created a hierarchy in terms of the protection afforded to these different types of copyrights. A creative work is entitled to the most protection, followed by a derivative work, and finally by a compilation. This is why the Feist Court emphasized that the copyright protection in a factual compilation is “thin.”

Not every court will agree with the idea that architectural floor plans are compilations, which makes developing tactics for an infringement case difficult. The takeaway for architects looking to use copyright to protect their designs is that while copyright protection is available and there are distinct benefits to registration with the Copyright Office, dealing with an infringement can be tricky. Should you find yourself the victim of an infringement, it is best to consult an intellectual property attorney before taking any kind of action.